|

Neel E.

Kearby

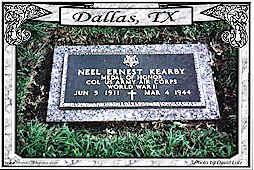

Probably the only thing about Neel

Kearby that didn't shout the name "Texan" was his

stature. Unlike the stereo-type: tall, rugged, fearless,

and filled with attitude--Neel stood only 5'9" tall.

The rest of him more than adequately fit the mold.

Born in the rural North Texas town of

Wichita Falls along the Oklahoma border in 1911, Neel was the

son of Dr. and Mrs. J. G. Kearby of Dallas. He grew up

in Arlington, a thriving metropolis sandwiched between Dallas

and Fort Worth, where he first attended high school and later

North Texas Agricultural College, before transferring to the

University of Texas at Austin. He graduated there in

1937 with a degree in Business Administration.

As a boy, Kearby had always been

fascinated with aviation. He earned his first flight by

agreeing to wash a neighbor's private plane. But

Kearby's interest was not only in flight, but in aerial

combat. His boyhood heroes were the pilots of the last

great war, the aces of World War I. He compiled a

personal collection of albums featuring the great aviators who

had inaugurated aerial warfare, and dreamed of someday being

like them. Such dreams compelled him to enlist as a

flying cadet after earning his degree, and he received his

commission as an Army Air Corps aviator in February 1938.

Neel Kearby was an easily likeable man,

reserved on the ground but a tiger in the air. From his early

days of learning to fly in aged AT-6 Army trainers in Texas in

1937, to his tour of duty flying P-39s in Panama during the

first year of World War II, Neel Kearby was known to take his

flying seriously--and competitively. In the cockpit he

was a skilled airman, cool under pressure, and driven to

excel. He was also a keen tactician and a natural leader.

By the time Kearby received orders to depart Panama and assume

command of the new 348th Fighter Group at Westover

Field, Massachusetts, in October 1942, he had risen to the

rank of Major in fewer than four years.

P-47

Thunderbolts

Under Major Kearby the 348th Fighter

Group began training for combat, equipped with the newest

advancement in fighter aircraft, the P-47. Built by

Seversky Aircraft Corporation (later renamed Republic

Aviation), the Thunderbolt was designed specifically

for the air war in Europe as an escort fighter for

high-altitude bombers. For this reason maneuverability

was sacrificed for greater fire-power, heavier armor, greater

durability, and a larger engine. The end-result was a

nearly 7-ton fighter framed within a bulky, barrel-shaped

fuselage. The ungainly airplane was quickly renamed the

"Jug" in derision by other pilots who saw it as ugly

and unsuitable for combat. To make matters worse,

the heavy fighter was very slow taking off and had a very poor

rate of climb . Other pilots joked that if Army

engineers built a runway all the way around the planet, "Republic

(Aviation) would build an airplane that needed every foot of

it (to get airborne.")

Neel Kearby the tactician looked beyond

the engineering nightmare that was the P-47 and found a

flying arsenal. Featuring eight, forward-firing, heavy

50-caliber machineguns, the Thunderbolt was a flying

warhead that could dive with impunity into the most fearsome

enemy formation and emerge unscathed. The P-47 was

designed to withstand a six-ton impact, making it virtually

indestructible. Kearby continued to acquaint himself with the

capabilities of the Thunderbolt and to train his pilots

to take advantage of the aircraft's natural abilities for the

high-altitude air war over Germany. By May his men were ready

for combat in Europe.

Meanwhile, in the Pacific, General

Kenney's P-38 pilots had been writing an impressive resume for

their fast, highly-maneuverable Lockheed Lightnings.

Outnumbered more than two-to-one by the Japanese less than a

year earlier, and supplemented primarily by aging and

battle-damaged P-39s and P-40s, Kenney's fighter pilots now

ruled the skies over eastern New Guinea.

|

Letters

were assigned to aircraft according to their mission

type, followed by numbers denoting their particular

model. Bomber aircraft, for instance, were

preceded by the letter "B", followed by

their model: B-17, B-24, B-25, etc.

During

World War I, fighter aircraft were called

"Pursuit Aircraft", and that designation

remained, thus fighter planes were denoted with the

letter "P" followed by their model: P-38,

P-38, P-40, P-47, etc.

| Other

designations included: |

- "A"

for Attack (Diver Bombers)

- "O"

for Observation Airplanes

- "C"

for Cargo Airplanes

|

- "G"

for Gliders

- "CG"

for Cargo Gliders

- "AT",

"BT", "PT" for Trainers

|

|

The

model number followed by a letter indicates

modifications to a particular model. A

"B-17G", for instance, indicated a

Bomber, model 17, in its

seventh ("G") modification.

Occasionally existing aircraft were modified

for other missions. A P-51 that

had been modified for dive bombing (attack)

missions, was re-designated an A-36.

|

|

The Fifth Air Force had played a key

role in the highly successful campaign to secure the north

side of the Papuan Peninsula and establish air bases east of

Lae, then had crushed the Japanese effort to reinforce Lae

during the Battle of the Bismarck Sea. Kenney's

Fifth Fighter Command was victorious but badly bruised.

In March 1943 General Kenney made his first visit to

Washington, D.C., since taking command of the Fifth Air Force

less than a year earlier. A key part of this trip,

beyond briefing Hap Arnold and the General Staff on the

progress in the Pacific, was to plead for replacement pilots

and new aircraft. The Fifth Air Force had accomplished

what a year earlier was considered impossible, but the toll

left the command worn, torn, bleeding, and struggling to keep

airplanes in the air. The combat toll had been so

extensive it was not unusual for more than half of the

aircraft mounted for a mission to be forced to abort, not

because of enemy fire, but because of mechanical failure.

Kenney quickly learned that among the

top Allied war planners, despite his tremendous success in the

Southwest Pacific, defeating the Japanese was a "war on

the back burner." Most Allied efforts were focused on

defeating the Axis in Europe. This was not a message

Kenney wanted to hear, or a decision he would accept. He

continued to plead for new pilots and aircraft, and the effort

finally paid off. On March 22, less than ten days before

Kenney's return to Port Moresby, Hap Arnold called him

to his office. He advised the Fifth Air Force commander

that he had "squeezed everything dry to give him some

help." That help was to come in the form of:

-

One new heavy bombardment group

-

Two and a half medium bombardment

groups

-

Three new fighter groups--and, "Oh,

one of those groups will have to be a P-47 group. No

one else WANTS them."

Desperate for anything, despite all the

negatives he had heard about the P-47, and ignoring his own

misgivings about the ungainly Jugs, Kenney said he

would gladly take ANYTHING Hap chose to send.

Major

Kearby took a badly-needed break from making his squadrons

ready for combat in Europe on April 3, two days after George

Kenney left Washington to return to his own command.

That seven-day leave gave Kearby the opportunity to spend a

little time with his children and his beautiful wife Virginia,

whom he affectionately called "Ginger." When

he returned to work on April 9, it was to find something

unusual going on. The 348th Fighter Group was

being readied for deployment. Major

Kearby took a badly-needed break from making his squadrons

ready for combat in Europe on April 3, two days after George

Kenney left Washington to return to his own command.

That seven-day leave gave Kearby the opportunity to spend a

little time with his children and his beautiful wife Virginia,

whom he affectionately called "Ginger." When

he returned to work on April 9, it was to find something

unusual going on. The 348th Fighter Group was

being readied for deployment.

Within 30 days the group moved to Camp

Shanks, New York, to begin their final preparations before

leaving for overseas combat. On May 14 both pilots and

planes were boarded on the Army Transport Henry Gibbons.

On May 21 the Henry Gibbons passed through the Panama

Canal, and the men aboard who were headed for war at last knew

what many had begun to suspect, that the 348th Fighter Group

with its P-47 Thunderbolts was not headed for Europe.

They were, in fact, the group no one else wanted that Hap

Arnold had promised General Kenney.

The 348th Fighter Group was headed for

war in the Pacific with their unwanted, untested, and

oft-derided, P-47s Thunderbolts.

|

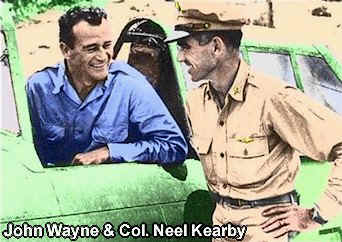

Lieutenant Colonel Neel Kearby

reported for duty with the Fifth Air Force at Brisbane, Australia, on

June 20. Meanwhile his ground crews and crated P-47s continued

on to their final destination further north at Townsville.

General Kenney recalled meeting Kearby for the first time quite well.

The newly-arrived group commander made a solid impression, not only

for his resume as a seasoned pilot with 2,000 hours of flight time

already on the books, but for his eagerness for combat. From the

moment of that first meeting, something clicked between the two

men, and they became very close friends.

Neel Kearby's boyhood heroes had

been the great aces of World War I, men who admired and hoped to

emulate. Perhaps Kenney saw in Kearby the same fire, ability, and

hunger that had marked one of those men, the pilot even Eddie

Rickenbacker had proclaimed the "the greatest airman of World

War I," the unstoppable Frank Luke. Kenney had flown

combat in that earlier war, shooting down his first German plane on

the same day Luke began his incredible string of aerial victories by

bagging three balloons in a day on September 15, 1918. Kenney

knew well the story of Luke's competitive personality, his daring

braggadocio, and the skill as a pilot that had enabled him to

accomplish what he proclaimed he would do. (In all, Kenney

netted two confirmed kills in World War I, earning the Distinguished

Service Cross for his second aerial victory on October 9.)

Kenney wrote of that

introduction: "Kearby, a short, slight, keen-eyed,

black-haired Texan about thirty-two, looked like money in the bank

to me. About two minutes after he had introduced himself he

wanted to know who had the highest scores for shooting down Jap

aircraft. You felt that he just wanted to know who he had to

beat."

In the summer of 1943 General

Kenney had plenty of seasoned heroes under his command of whom he

could be...and was...justifiably proud. There was Captain George

Welch who had shot down four Japanese airplanes at Pearl Harbor on

December 7, 1941, earning him the Distinguished Service Cross.

Still knocking down enemy airplanes, Welch scored his ninth victory

the day after Kearby reported.

Captain Tom Lynch and First

Lieutenant Richard Bong were tied at eleven victories each, and looked

to be poised for many, many more. The previous December, Eddie

Rickenbacker himself had visited the Fifth Air Force, promising to

match Kenney's proffered case of Scotch to the first airman to beat

the World War I Ace of Aces' unequalled twenty-six aerial

victories. Kenney had no doubt that one of his young pilots

would eventually reach that benchmark, and any one of his three

veteran aces was capable. But Kenney recognized a difference in

the attitude of the young Lieutenant Colonel before him, who had

reported for duty by inquiring who he had to beat for the top spot on

the victory list.

Though Welch, Lynch, and Bong

were each capable of breaking Rickenbacker's record, none of the three

felt pressured to do so. For them, aerial combat was a daily job

of shooting down enemy planes. Theirs' was not a race to the

top. They were simply doing a job to be done, and they were all

three very good at doing their jobs. Neel Kearby, on the other

hand, had a hunger in his eyes. It was a drive perhaps fueled by

his boyhood adoration of the World War I top guns, coupled with

the boyhood dream to emulate, and even exceed, the accomplishments of

his personal heroes. Beyond the hunger that fueled his intensely

competitive spirit, Lieutenant Neel Kearby had both the skill and

tactical prowess to accomplish his goals. Perhaps the only real

difference between Neel Kearby and the great balloon-buster

Frank Luke was that, while Luke's braggadocio turned off his fellow

pilots and relegated him to being a lone-wolf, Kearby was an easily

likable man. No one, least of all General Kenney, took offense

when the 348th Group commander began to proclaim that he intended to

shoot down FIFTY Jap planes.

Of course, before Kenney's newest

would-be ace could get started, General Kenney had to get him

into combat. That, despite Kearby's eagerness, was no small

matter. First and foremost, it would take a month to assemble

the crated P-47s at Townsville. Once assembled, the small fuel

tanks would limit the range of combat operations, necessitating

additional delays until supplemental "wing tanks" could be

manufactured and installed. To further complicate matters, the

veteran pilots of the Fifth Fighter Command weren't all that confident

that the P-47 Thunderbolts were even capable of combat

operations.

| "Everyone

in the 5th Air Force, from (General) Whitehead and (General)

Wurtsmith down, except the kids in the new (348th) group,

decided that the P-47 was no good as a combat plane. Besides

not having enough gas, the rumors said it took too much

runway to get off, it had no maneuverability, it would not

pull out of a dive, the landing gear was weak, and the

engine was unreliable.

"I sent for Kearby

and told him I expected him to sell the P-47 or go back

home. I knew it didn't have enough gas but we would hang

some more on somehow and prove it as a combat plane,

especially as it was the only fighter that (Hap) Arnold

would give me in any quantities for some time.

"I told Kearby that,

regardless of the fact that everyone in the theater was sold

on the P-38, if the P-47 could demonstrate just once that it

could perform comparably I believed that the 'Jug,' as the

kids called it, would be looked upon with more favor.

I told him that Lieutenant

Colonel George Prentice would arrive that afternoon from New

Guinea to take command of the new P-38 group which I had

formed and had started training at our Amberley Field.

He would probably celebrate a little tonight. I told

Neel to keep away from Prentice, go to bed early, and the

first thing in the morning to hop over to Amberley in his

P-47 and challenge Prentice to a mock combat. Neel

Kearby was not only a good pilot but he had several hundred

hours' playing time with a P-47 and could do better with it

than anyone else. Prentice was an excellent P-38

pilot, but for the sake of my sales argument I hoped he

wouldn't be feeling in tiptop form when he accepted Neel's

challenge.

General

George C. Kenney

General Kenney Reports

|

It was this critical situation

that led to the early morning of mock-combat over Amberley where

General Kenney's gamble paid off, resulting in Kearby shooting

down Prentice's P-38 several times. Kenney, for his own

part, was pleased with the outcome and quick to nix any hopes for a

rematch. The single clash between P-38 and P-47 had achieved

its necessary goal. In a rematch, with Prentice at the top of

his form, the results might be reversed.

For the moment it was

sufficient to know that at last the Thunderbolts had been

accepted, even if still dubiously so, as a part of the combat

inventory of the Fifth Air Force. The real test would come

later, when they faced the Japanese in the air. Kenney could

only hope that the P-47 would again prove itself a capable fighter,

despite its many deficiencies.

During the last week of July

Lieutenant Colonel Kearby began moving his fighter squadron to Port

Moresby. Even as they were arriving, Kearby's competition was

growing. On July 26 Lieutenant Bong had his single-best day of

the war, shooting down four enemy planes and earning the

Distinguished Service Cross. Two days later he bagged another,

bringing his score to sixteen.

If Dick Bong wasn't counting,

Neel Kearby certainly was. He saw his competition increase at

the same time he and his men were relegated to generally uneventful

duty at Port Moresby, missions that offered little chance for

combat. Kearby's P-47s were still on a short leash for lack of

supplementary wing tanks. Besides that fact, the

slow-to-takeoff Jugs made them well-suited to the defense of

Port Moresby. Radar provided up to an hour of advance warning

before incoming bogies arrived and, even at their slow climb speed,

an hour was ample to get the Thunderbolts in position to meet

an incoming Zero or bomber.

During the first two weeks of

August the Japanese began reinforcing New Guinea by moving hundreds

of fighters into airfields west Lae, on the north coast of the

island, in and around Wewak. Kenney responded at mid-month

with the most sweeping raids since the Battle of the Bismarck Sea.

It was during these missions on August 18 that Major Ralph Cheli was

shot down while piloting his B-25, earning him a posthumous Medal of

Honor.

That same day, a new would-be top

gun with a fire akin that which burned within Neel Kearby, got

his first, and second...and THIRD victory. Two days later the

newly arrived Tommy McGuire became an ace in his P-38.

Dick Bong missed the action

around Wewak in mid-August when the Fifth Fighter Command had some

of its best hunting. The leading Army ace in the Southwest

Pacific had suffered battle damage in a July 28 mission, and his

plane was out for repairs. Kenney promoted Bong to Captain and

sent him to Australia for R & R while his P-38 was being

repaired. In Bong's absence, Tom Lynch took up the slack,

shooting down two enemy on August 20 and bringing his own total to

fourteen. He scored another victory the following day.

While Kenney's Lightnings

had a "field day" in the skies over the Huon Gulf and

around the airfields near Wewak in the latter weeks of August,

Kearby's Thunderbolts continued to fly nondescript

missions--protection patrols at Port Moresby and Dobodura, and

routine convoy escort operations. The one piece of good news

in the month came on August 16 when sixteen P-47s flying close

escort duty for Army transports bound for Marilinan were attacked by

a dozen enemy Oscars. Captain Max Wiecks and Lieutenant

Leonard Leighton each scored a victory, the first for the 348th

Fighter Group.

Lieutenant Leighton was himself

shot down, and was last seen parachuting into the jungle below.

Several months later an Allied patrol found his body, confirming him

as the Group's first combat casualty.

When the month of August ended,

Dick Bong was in Australia, Tom Lynch was two victories behind Bong

with fourteen kills, and the rookie Tommy McGuire's tally was up to

seven. Lieutenant Colonel Neel Kearby, who had yet to prove

the true value of his P-47s despite the Groups two victories, was

still fifty victories shy of the mark he had set for himself.

And for the most part, Kearby and his pilots were still stuck in

convoy escort duty, far from the fertile hunting grounds

around Wewak.

September 4, 1943

First Blood

After the fall of Buna and Gona

in January, Allied attention focused on routing the last Japanese

stronghold at Lae, near the Huon Gulf. Early in the Spring

General Kenney established an airfield at Tsili Tsili, just forty

miles from the large and critical port of Lae. Then, on

September 3, he dispatched twenty-three heavy bombers to unload 84

tons of bombs on Lae's gun defenses while nine strafers followed

with more than 500 fragmentation bombs and 35,00 rounds of

machine-gun fire. It was preparation for the final showdown to

at last capture Lae.

The

following morning two dozen B-24s dropped another 96 tons of bombs

on Lae. Meanwhile Major General Wooten's 9th Australian

Division, departing out of Buna, landed in U.S. Navy LSTs on Hopoi

Beach a short distance east of Lae. The invasion date had been

selected based on suitable weather, cloud cover and fog to keep

enemy planes based on nearby New Britain Island from interfering

with the landing. Unfortunately, that same weather

masked events on the surface of the ocean from the fighter cover

flying just above the haze. When the transports neared the

beach, enemy shore batteries opened up with a withering fire.

Simultaneously, enemy airplanes hidden in the nearby jungle managed

to slip in beneath the haze to attack the landing force. The

following morning two dozen B-24s dropped another 96 tons of bombs

on Lae. Meanwhile Major General Wooten's 9th Australian

Division, departing out of Buna, landed in U.S. Navy LSTs on Hopoi

Beach a short distance east of Lae. The invasion date had been

selected based on suitable weather, cloud cover and fog to keep

enemy planes based on nearby New Britain Island from interfering

with the landing. Unfortunately, that same weather

masked events on the surface of the ocean from the fighter cover

flying just above the haze. When the transports neared the

beach, enemy shore batteries opened up with a withering fire.

Simultaneously, enemy airplanes hidden in the nearby jungle managed

to slip in beneath the haze to attack the landing force.

LST 473 was approaching the

beach with its cargo of Australian infantrymen, tanks and supplies

even as a torrent of deadly shells erupted in the waters around it.

The transport continued its course towards the beach, determined to

brave the maelstrom. Suddenly one of the Japanese dive bombers

came in low and released a torpedo directly into the path of the

landing craft. Seaman First Class Johnnie David Hutchins

glanced quickly to the pilothouse to warn the steersman when, in an

instant, a bomb shattered LST 473. The explosion killed the

steersman and mortally wouded Seaman Hutchins, leaving the barge

nearly dead in the water. LST 473 was helpless and the ship and the

men it carried were doomed by the incoming torpedo.

With

only seconds to react, and with the last vestiges of life vanishing

from his battered body, somehow Johnnie Hutchins managed to stagger

to the wheel and turn the ship clear of the torpedo's path.

Then he died, still clinging to the wheel. With

only seconds to react, and with the last vestiges of life vanishing

from his battered body, somehow Johnnie Hutchins managed to stagger

to the wheel and turn the ship clear of the torpedo's path.

Then he died, still clinging to the wheel.

Around him combat-hardened

Australian soldiers who had seen the act were awed by the sheer

resolve and determination they had witnessed. They could not

forget the smiling, blond, 21-year-old sailor from Texas who had

sacrificed his last ounce of ebbing strength to save their lives.

One year later at the Sam Houston Coliseum in Houston, Texas, Rear

Admiral A. C. Bennett presented Johnnie Hutchin's well-deserved

Medal of Honor to his mother.

Despite the hail of enemy fire

from the beach, General Wooten's Rats of Tobruk, so-named for

their own heroic stand a few years earlier in North Africa, landed

together with their tanks and supplies. Before noon the

transport convoy began the return trip to Buna, save for Johnnie

Hutchins' and one other transport so damaged that it would only get

as far as the port at Morobe.

The returning convoy was faced

with new dangers when the afternoon sun burned off the haze,

exposing the ships to enemy flights out of New Britain. At the

airfield at Dobodura near Buna, Lieutenant Colonel Neel Kearby was

unaware that enemy pilots had killed a fellow Texan, but he was well

aware that a fight was brewing. Word reached Dobodura that

enemy aircraft had been sighted moving into the Morobe, Salamua, and

Finchhafen areas, which were near the invasion site at Hopoi Beach.

It was the anticipated enemy response to the landing of Australian

troops on the doorstep of their fortress at Lae.

Kearby's Thunderbolts

began taking off around two o'clock in the afternoon, Yellow Flight

from the 342d Squadron, followed by seven more airplanes of Blue and

Green Flights. The last flight of twenty P-47s was led by the

Group commander himself.

Half-an-hour later Kearby's

formation of four fighters were fourteen miles south of Hopoi Beach,

cruising easily at 25,000 feet, when Neel saw what appeared to be

two fighters and a flying boat flying close-formation miles below.

At that distance it was impossible to identify the bogeys and Kearby

knew if he dove, he would lose precious altitude that would be

difficult to recover if the dark blips beyond turned out to be

American. Kearby noted the signs of bomber damage around

Morobe and several fires in the water near Cape Ward Hunt, and

decided the possibility that the unidentified airplanes were enemy

made it worth the risk. With his wing man trailing, he nosed

into a steep dive at more than 400 miles per hour, closing the gap

in less than a minute.

At 2,000 feet Kearby and

Lieutenant George Orr, his wingman, closed to within three-hundred

yards behind and to the left of the three aircraft. The large

flying boat in the center was a Betty bomber, protected by a

Zero and an Oscar close on each wing. The red orbs of the

rising sun confirmed their identity as Japanese.

Adrenaline filled every fiber

of the would-be super-ace at the prospect of his first combat.

Perhaps it was buck fever, it was doubtless NOT by design,

that rather than making a nearly sure-shot at one plane, Neel Kearby

unleashing his eight 50-caliber machineguns on two enemy at once.

Even before Lieutenant Orr could trigger his own guns, the wing-man

watched in amazement as the Betty bomber exploded. One

wing ripped away from one of the escorting fighters, causing it to

also plunge into the sea below. Kearby knew he had been

lucky--his first victory had been a double-punch. Chalk one up

for the highly-touted increased firepower of the P-47. There

could be no more doubts.

The P-47s zipped past the

flaming, falling debris that had been two enemy planes before they

could sight on the third fighter. Struggling against the

inertia of their diving seven-ton Thunderbolts, Kearby and

Orr banked and tried to pursue the now vanishing Oscar. Kearby

tried to line up for a third kill, but the Japanese pilot executed a

nimble climb, leaving Kearby's sights filled only with blue sky and

white clouds.

Nearly thirty enemy aircraft

were destroyed on September 4, six by the anti-aircraft guns in the

convoy, twenty-one of them by General Kenney's P-38s. Neel

Kearby scored the only victories for the 348th squadron. Kearbyy

also realized that his over-eagerness had disrupted what could have

been a near-perfect attack, one that would have netted all three

enemy planes.

The keen tactician mentally

noted his mistakes, which could not take away from his celebratory

mood upon returning to Ward's Drome. Not only was he at last

in the race for Top Gun, he had demonstrated the soundness of

a tactic he had preached to his pilots since they received the first

P-47s back in the states. Despite its weight, its clumsiness

at low altitudes, and its slow rate of climb, the Thunderbolt

could be deadly when tactically deployed. Kearby would leave

it to lighter, more nimble fighters to dog-fight at low altitudes.

Proper use of the Thunderbolt meant free-roving flights at

high altitude, where they were designed to fly, and where they could

track enemy formations unseen. When the moment came for combat

the Thunderbolt's unequalled diving speed would put its guns

within range of destroying that formation, long before the enemy

even knew American pilots had spotted them.

The battle for Lae was the

focus of the Fifth Air Force efforts for nearly two weeks. On

September 5 Kenney's bombers continued to pound enemy positions in

support of the ground operations. This further including dropping

Australian paratroopers into Nadzab west of Lae. For the

Australians, it was their first jump ever. After a last-minute

decision to insert them by air, their pre-jump training had

consisted of nothing more than brief instructions on how to pull the

ripcord that deployed the chutes. The operation was

surprisingly successful and by nightfall Nadzab was in Allied hands.

The following day air

operations continued with Fifth Air Force C-47 transports flying

General Vasey's 7th Australian Division into Nadzab. To

protect the troop movement, bombers continued to pound enemy

fortifications around Lae, and fighters did their best to keep enemy

aircraft out of the battle. Dick Bong, recently returned from

Australia, claimed two more enemy aircraft shot down. Neither

was ever confirmed or added to his score--which is ironic. If

Dick Bong claimed he shot something down, it was no exaggeration.

The intrepid Captain had a reputation, not of padding his score, but

of frequently giving credit for his own victories to other pilots.

Unfortunately, on returning to Marilinan airfield, Bong made a

difficult crash landing. Though he survived uninjured, he was

again temporarily out of action.

The ground combat to take Lae

continued unabated and with great success by the determined

Australians in the week following the landings at Hopoi Beach and

Nadzab. Air operations, on the other hand, were greatly

hampered by a week of poor weather. Towards mid-month the

weather began to clear slightly, and increased air combat followed.

Neel Kearby's double victory on September 4 brought to four the

total number of aerial victories for his fighter group. On

September 13 Major Bill Banks and Lieutenant Larry O'Neill each

scored while flying routine transport cover, upping the P-47 tally

to six.

The following day, while

leading a similar mission at 20,000 feet near Nadzab, an

unidentified aircraft was spotted about 9:45 a.m. above and to the

right of Kearby's formation. When the bogey saw the American

planes it began a desperate race for the clouds, a quick indication

to Kearby that it was enemy.

Kearby's P-47s were now

operating with disposable drop tanks to extend their range.

These supplemental fuel cells were normally released only before

combat, at which time they were lost forever. Realizing he was

still short of drop tanks, Kearby ordered his other pilots not to

drop their tanks. Instead, he would drop his own and pursue

the enemy alone. It was too late. With an eagerness for

combat that Kearby could now identify with, six of his seven pilots

had already dropped their tanks to follow their commander into

combat. (Kearby later learned that the seventh pilot would

have dropped his as well, but the mechanism jammed.)

Kearby got there first, closing

in at three-hundred yards on what he could now identify as a

Japanese Dinah. A single, three-second burst from eight

machineguns sent the enemy plane down in flames, and Kearby had

upped his score to three. It would be his last for the month,

indeed the last for a dry spell lasting nearly 30 days.

Meanwhile, in that first full month of combat, his Thunderbolt

fighter group had claimed eleven confirmed victories, at least

another dozen probable but unconfirmed, and with the loss of only

two of their own.

On the day Neel Kearby got his

third victory, Tom Lynch became a triple-ace. The following

day, September 16, while the Australian forces marched victoriously

into Lae, Lynch scored again. He was now tied at sixteen with

Dick Bong, who was returning to action.

Before Bong pulled back into

the lead with his seventeenth victory on October 2, Tommy McGuire

had upped his own score to seven, with two victories on September

28. Despite the dry spell for all of them over the following

week, things were shaping up to erase any lingering doubts about the

combat prowess of the P-47 Thunderbolt.

|

It was late June, 1943, and a lone American P-38 Lightening circled leisurely over Amberley Field near Townsville, Australia. In the cockpit was Lieutenant Colonel George Prentice, a solid combat veteran with two aerial victories, including one shoot-down four months earlier during the critical Battle of the Bismarck Sea.

Then, seemingly out of nowhere, a second fighter appeared. Incredibly the invader was diving from ABOVE...instantly and with deadly precision, in a lethal attack on Colonel Prentice's P-38. Powered by a single, 2,400-horse-power radial engine and with the added inertia of a seven-ton monster of a fighter plane, the attacker screamed in for the kill at more than 400 miles per hour. Four large machineguns were mounted on each wing, every one of them ready to fill the doomed P-38 with hundreds of 50-caliber rounds in less than a minute. Looking out his cockpit window, Lieutenant Colonel Prentice cursed his over-confidence, winged over, and tried to shake the barrel-shaped behemoth off his tail. It was too late--the attacking enemy couldn't be shaken.

Major

Kearby took a badly-needed break from making his squadrons

ready for combat in Europe on April 3, two days after George

Kenney left Washington to return to his own command.

That seven-day leave gave Kearby the opportunity to spend a

little time with his children and his beautiful wife Virginia,

whom he affectionately called "Ginger." When

he returned to work on April 9, it was to find something

unusual going on. The 348th Fighter Group was

being readied for deployment.

Major

Kearby took a badly-needed break from making his squadrons

ready for combat in Europe on April 3, two days after George

Kenney left Washington to return to his own command.

That seven-day leave gave Kearby the opportunity to spend a

little time with his children and his beautiful wife Virginia,

whom he affectionately called "Ginger." When

he returned to work on April 9, it was to find something

unusual going on. The 348th Fighter Group was

being readied for deployment.

The

following morning two dozen B-24s dropped another 96 tons of bombs

on Lae. Meanwhile Major General Wooten's 9th Australian

Division, departing out of Buna, landed in U.S. Navy LSTs on Hopoi

Beach a short distance east of Lae. The invasion date had been

selected based on suitable weather, cloud cover and fog to keep

enemy planes based on nearby New Britain Island from interfering

with the landing. Unfortunately, that same weather

masked events on the surface of the ocean from the fighter cover

flying just above the haze. When the transports neared the

beach, enemy shore batteries opened up with a withering fire.

Simultaneously, enemy airplanes hidden in the nearby jungle managed

to slip in beneath the haze to attack the landing force.

The

following morning two dozen B-24s dropped another 96 tons of bombs

on Lae. Meanwhile Major General Wooten's 9th Australian

Division, departing out of Buna, landed in U.S. Navy LSTs on Hopoi

Beach a short distance east of Lae. The invasion date had been

selected based on suitable weather, cloud cover and fog to keep

enemy planes based on nearby New Britain Island from interfering

with the landing. Unfortunately, that same weather

masked events on the surface of the ocean from the fighter cover

flying just above the haze. When the transports neared the

beach, enemy shore batteries opened up with a withering fire.

Simultaneously, enemy airplanes hidden in the nearby jungle managed

to slip in beneath the haze to attack the landing force. With

only seconds to react, and with the last vestiges of life vanishing

from his battered body, somehow Johnnie Hutchins managed to stagger

to the wheel and turn the ship clear of the torpedo's path.

Then he died, still clinging to the wheel.

With

only seconds to react, and with the last vestiges of life vanishing

from his battered body, somehow Johnnie Hutchins managed to stagger

to the wheel and turn the ship clear of the torpedo's path.

Then he died, still clinging to the wheel.

In

fact the enemy had ALREADY risen to the bait. Lieutenant Colonel Tamiya

Teranishi, commander of the Japanese 14th Fighter/Bomber group, was visiting

Wewak when radar picked up the incoming Thunderbolts from fifty miles

out. He ordered numerous fighters airborne from their fields in the

vicinity, then climbed in an Oscar himself and took off to lead the

intercepting force. Once rendezvoused with the other fighters he had

called into action, his flight would number more than two dozen armed

fighters: nimble Oscars and deadly Tonys.

In

fact the enemy had ALREADY risen to the bait. Lieutenant Colonel Tamiya

Teranishi, commander of the Japanese 14th Fighter/Bomber group, was visiting

Wewak when radar picked up the incoming Thunderbolts from fifty miles

out. He ordered numerous fighters airborne from their fields in the

vicinity, then climbed in an Oscar himself and took off to lead the

intercepting force. Once rendezvoused with the other fighters he had

called into action, his flight would number more than two dozen armed

fighters: nimble Oscars and deadly Tonys.

At

the same time General Kenney submitted his report verifying Kearby's

six single-day victories in support of a recommendation for the Medal

of Honor, Kearby was promoted to Colonel. In the weeks that

followed Neel pushed himself, not only to try and catch the elusive

Dick Bong, but to achieve his personal goal of fifty aerial victories.

Five days after his big day over Wewak, Kearby upped his score to ten.

He brought it to a dozen with a double victory on October 19.

At

the same time General Kenney submitted his report verifying Kearby's

six single-day victories in support of a recommendation for the Medal

of Honor, Kearby was promoted to Colonel. In the weeks that

followed Neel pushed himself, not only to try and catch the elusive

Dick Bong, but to achieve his personal goal of fifty aerial victories.

Five days after his big day over Wewak, Kearby upped his score to ten.

He brought it to a dozen with a double victory on October 19.  General

Kenney did attempt to slow Kearby down, fearful that the intense drive

that pushed the young pilot nearly beyond reason would ultimately

become his downfall. More and more he tried to keep Colonel

Kearby occupied with administrative duties, but there was no keeping

the man who wanted to be the greatest fighter pilot all time out of

the air. Kenney noted the difference between the personalities

of Kearby and Bong when he wrote his memoirs after the war.

General

Kenney did attempt to slow Kearby down, fearful that the intense drive

that pushed the young pilot nearly beyond reason would ultimately

become his downfall. More and more he tried to keep Colonel

Kearby occupied with administrative duties, but there was no keeping

the man who wanted to be the greatest fighter pilot all time out of

the air. Kenney noted the difference between the personalities

of Kearby and Bong when he wrote his memoirs after the war.