CHAPTER VIII

THE LEYTE OPERATION

The Leyte operation was to be the crucial battle of the war in the Pacific. On its outcome would depend the fate of the Philippines and the future course of the war against Japan. Located in the heart of the archipelago, Leyte was the focal point where the Southwest Pacific forces of General MacArthur were to converge with the Central Pacific forces of Admiral Nimitz in a mighty assault to wrest the Philippines from the hands of the enemy. (Plate No. 56) With Leyte under General MacArthur's control, the other islands would be within effective striking distance of his ground and air forces. Leyte was to be the anvil against which he would hammer the Japanese into submission in the central Philippines, the springboard from which he would proceed to the conquest of Luzon for the final attack against Japan itself. Military necessity demanded that the Allies achieve a decisive victory on Leyte. General MacArthur and Admiral Nimitz were committed to employ the maximum resources at their command.

It was axiomatic, too, that the Japanese would fight to the bitter end to save the Philippines. The war situation had grown progressively worse for Japan and by the autumn of 1944 her position was both critical and desperate. No longer were the Allies held at the outer periphery of her defense system. They were now poised with their full power at the very threshold of her inner structure and if they should break through, the Homeland itself would stand dangerously exposed-an inviting target for the next invasion. With the initiative entirely in Allied hands, the war had reached that decisive stage where another important Japanese defeat would seal the ultimate fate of Japan's Empire, and destroy a centuries-old tradition of invincibility. The Philippines would probably offer the last chance for the Japanese Army to recover its lost prestige and gain a victory over General MacArthur's forces. To achieve this victory, the Japanese battle fleet would undoubtedly come forth in full strength to throw back all invasion efforts. If the Japanese were to realize the rapidly diminishing hope of stemming the surging American tide, the decisive battle would have to be in the Philippines. The alternative of failure would be inevitable defeat. The decision had to be pressed.

The plan for the ground operations in the capture of Leyte comprised four main phases. Phase One covered minor preliminary landings to secure the small islands lying across the entrance to Leyte Gulf. Phase Two included the main amphibious assaults on Leyte from Dulag to Tacloban and called for the seizure of the airstrip, an advance through Leyte Valley, and the opening of San Juanico and Panaon Straits. Phase Three consisted of the necessary overland and shore-to-shore operations to complete the capture of Leyte and the

[196]

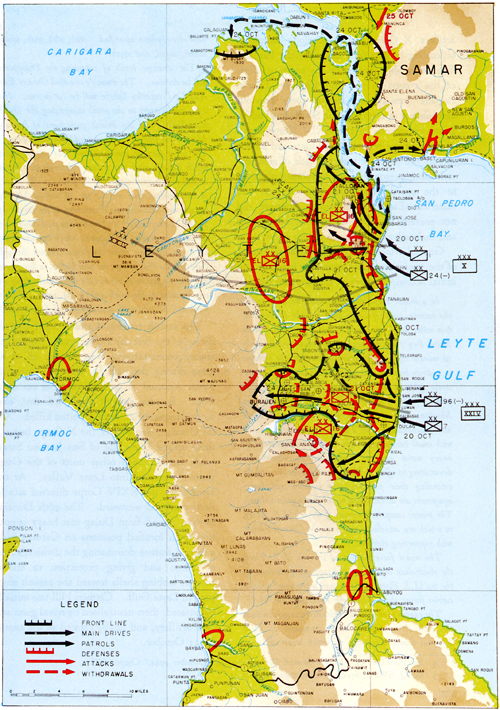

PLATE NO. 56

Leyte

[197]

seizure of southern Samar. Phase Four contemplated the occupation of the remainder of Samar and the further neutralization of enemy positions in the Visayas.

The first landings to mark the invasion of the Philippines were made on three small islands which guarded the eastern approaches to Leyte Gulf. Despite cyclonic storms and heavy seas, elements of the 6th Ranger Battalion, augmented by one company of the 21st Infantry, went ashore on Suluan and Dinagat Islands on 17 October 1944. (Plate No. 57) Heavy mists shrouded their approach and they were opposed only by the rough surf and battering winds. Homonhon Island was occupied the next day. All three islands were quickly cleared. of small enemy garrisons and radio installations while mine sweepers and demolition teams co-operated to sweep the waters and the beaches of all obstacles potentially dangerous to the main operation.

On 20 October, the largest mass of naval assault craft and warships ever concentrated in the Pacific sailed boldly into Leyte Gulf. The landing beaches and tactically important rear areas had already been softened by a continuous two-day ship and plane bombardment.1 After an additional morning barrage, the landing troops were ready to go ashore.

The main assault on the east coast of Leyte began at ten o'clock in the morning with landings along an 18-mile front between the two small villages of Dulag and San Jose. X Corps, comprising the 1st Cavalry and the 24th Divisions, covered the right flank of the landings to the north; XXIV Corps, consisting of the 7th and 96th Divisions, secured the left flank. Both shores of Panaon Strait at the southern tip of the island were seized by a single regimental combat team of the 21st Infantry which had gone ashore an hour prior to the main assault.

General MacArthur's stirring promise to return to the Philippines was fulfilled shortly after the main landings. In a drenching rain he strode ashore on the muddy beachhead near Palo, following close to the assault echelons, and heralded the coming hour of liberation. Speaking to millions of waiting Filipinos over a portable radio set, he declared

This is the Voice of Freedom, General MacArthur speaking. People of the Philippines: I have returned. By the grace of Almighty God our forces stand again on Philippine soil-soil consecrated in the blood of our two peoples. We have come, dedicated and committed to the task of destroying every vestige of enemy control over your daily lives, and of restoring, upon a foundation of indestructible strength, the liberties of your people.

At my side is your President, Sergio Osmena, worthy successor of that great patriot, Manuel Quezon, with members of his cabinet. The seat of your government is now therefore firmly re-established on Philippine soil.

The hour of your redemption is here. Your patriots have demonstrated an unswerving and resolute devotion to the principles of freedom that challenges the best that is written on the pages of human history.

[198]

I now call upon your supreme effort that the enemy may know from the temper of an aroused and outraged people within that he has a force there to contend with no less violent than is the force committed from without.

Rally to me. Let the indomitable spirit of Bataan and Corregidor lead on. As the lines of battle roll forward to bring you within the zone of operations, rise and strike! For future generations of your sons and daughters, strike! In the name of your sacred dead, strike! Let no heart be faint. Let every arm be steeled. The guidance of Divine God points the way. Follow in His name to the Holy Grail of righteous victory!2

Opposition at the landing beaches was negligible and first-day casualties resulted primarily from a few well-placed mortar and artillery pieces that remained unsilenced by the preliminary air and naval bombardment. In the San Jose sector, the X Corps advanced quickly and by midafternoon the 1st Cavalry Division, supported by tanks, had secured Tacloban Airfield, the most important early objective.3

At the same time, the 24th Division pressed forward, fighting its way inland in the area of the Palo-Tacloban Highway. (Plate No. 58) The objective in this sector was a height dominating the entire landing beach area near Palo labeled Hill 522. As this hill commanded both the highway system and the beaches, the Japanese had fortified it with trenches, caves, and cleverly concealed emplacements that would offer serious opposition to an attacking force. A slight but serious miscalculation on the part of the enemy, however, enabled the 24th Division to seize the hill with a minimum of loss. The severity of the naval, air, and artillery bombardment had forced the Japanese to leave their guns and take temporary refuge in the safer ground below. As soon as the shelling stopped, they began their move back up the slopes to reoccupy their commanding positions and open fire on the advancing Americans. They were too late. So swift was the progress of the invading forces, that troops of the 24th Division were already on the crest of the hill to meet and destroy the returning enemy.

In the Dulag sector, which was the responsibility of the XXIV Corps, the 96th Division advanced against stiffening resistance but by early afternoon it had carried its attack inland from x ,000 to 3,000 yards. On the left flank of the Corps, the 7th Division encountered little initial opposition after the landing and pushed steadily forward to secure Dulag airdrome on 21 October. The airfield, however, situated as it was in the flat, flood plain of the Marabang River, was not suitable for immediate use. Poor drainage, numerous small swamps, and the thick, sedimentary silt of the plain rendered the airstrips generally unusable until well toward the end of November.

In the X Corps sector, unloading was delayed by unfavorable terrain to the rear of the beach. Although sporadic enemy mortar and artillery fire hampered the fast discharge of LST cargo and landing of needed

[199]

PLATE NO. 57

Sixth Army Landings on Leyte, 17-20 October 1944

[200]

PLATE NO. 58

Leyte Assault, 20-25 October 1944

[201]

artillery, X Corps assault echelons completed unloading by the fifth day after the landing. They were ably assisted by the untiring efforts of the troops of the 2nd Engineer Special Brigade, veterans of almost every previous amphibious operation in the Southwest Pacific. Beach conditions in the XXIV Corps sector varied, but the presence of snipers and enemy mortar fire together with the lack of sufficient unloading personnel were temporary obstacles to the speedy disembarkation of men and materiel. Delay in unloading, however, did not prevent the establishment of beachheads and early advances inland by both corps.

General MacArthur, in personal command of the operation, summarized the landings and initial accomplishment of the invasion forces:

In a major amphibious operation we have seized the eastern coast of Leyte Island in the Philippines, 600 miles north of Morotai and 2,500 miles from Milne Bay from whence our offensive started nearly 16 months ago. This point of entry in the Visayas is midway between Luzon and Mindanao and at one stroke splits in two the Japanese forces in the Philippines. The enemy's anticipation of attack in Mindanao caused him to be caught unawares in Leyte and beachheads in the Tacloban area were secured with small casualties. The landing was preceded by heavy naval and air bombardments which were devastating in effect. Our ground troops are rapidly extending their positions and supplies and heavy equipment are already flowing ashore in great volume. The troops comprise elements of the 6th U. S. Army, to which are attached units from the Central Pacific, with supporting elements.

The naval forces consist of the 7th U. S. Fleet, the Australian Squadron, and supporting elements of the 3rd U. S. Fleet. Air support was given by naval carrier forces, the Far East Air Force, and the RAAF. The enemy's forces of an estimated 225,000 include the 14th Army Group under command of Field Marshal Count Terauchi, of which seven divisions have already been identified: 16th, 26th, 30th, 100th, 102nd, 103rd, and 105th.4

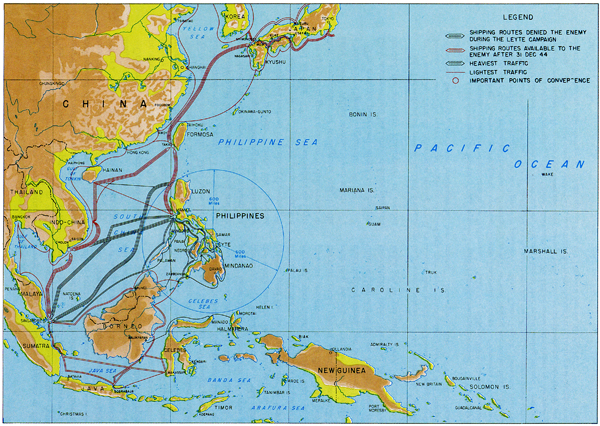

The strategic result of capturing the Philippines will be decisive. The enemy's so-called Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere will be cut in two. His conquered empire to the south comprising the Dutch East Indies, and the British possessions of Borneo, Malaya and Burma will be severed from Japan proper. The great flow of transportation and supply upon which Japan's vital war industry depends will be cut as will the counter supply of his forces to the south. A half million men will be cut off without hope of support and with ultimate destruction at the leisure of the Allies a certainty. In broad strategical conception the defensive line of the Japanese which extends along the coast of Asia from the Japan Islands through Formosa, the Philippines, the East Indies, to Singapore and Burma will be pierced in the center permitting an envelopment to the south and to the north. Either flank will be vulnerable and can be rolled up at will.5

The assault continued after a rapid consolidation of the first day's objectives. Numerous enemy counterattacks were beaten off in all areas during the next few days as advancing forces reported increased resistance on every front. By the end of the third day, over 2,000 Japanese had been reported killed. On 24 October, elements of the X Corps began a drive up the Leyte side of San Juanico Strait, while farther south other units of the Corps pushed westward into Leyte Valley. At the same time, the XXIV Corps directed attacks northward and westward. The 96th Division moving inland from Dulag met heavy opposition from fortified positions on Catmon Hill, a terrain feature dominating the division's zone of action and giving protection to enemy mortars lobbing shells toward the assault shipping in Leyte Gulf. Catmon Hill was initially by-passsed, then neutralized by naval guns and field artillery, and finally cleared of the enemy by 31 October.

[202]

Recognition of the effort by all arms was contained in General MacArthur's report of 25 October 1944:

Our ground forces have made extensive gains in all sectors. On the front of the XXIV Corps ... the 7th Division penetrated the enemy's covering screen to seize San Pablo airdrome and fan out to the north toward Dagami. Elements of the 96th Division ... have enveloped Catmon Hill and are approaching Tabontabon. In the northern sector, the X Corps has made substantial gains to the west of Palo and Tacloban and is pushing forward from the line of hills seized from the enemy which dominate the coast between Palo and Tacloban.

Carrier aircraft of the Seventh Fleet executed close support missions, attacking enemy ground installations, supply dumps and lines of communication. On October 22 and 23, our planes struck enemy airdromes in the western Visayas and northern Mindanao. Targets included Cebu, Bacolod, Alicante, Fabrica, Buluan and Del Monte.... Our successive raids from all sources on the enemy's air installations are neutralizing his attempts at staging in aircraft from Luzon and Borneo, and have greatly restricted the scale of his air counteroffensive ....6

While the Allies were fighting to improve their beachheads on Leyte, the Japanese were preparing to stake their whole remaining striking power on a gigantic gamble to maintain their positions in the Philippines.7 The role of the Combined Fleet in this critical battle was vital. Brilliantly conceived and immense in scope, the Japanese plan was to deliver a crippling attack against the U. S. Navy and, with the strategic situation in their favor, to destroy in the same stroke General MacArthur's invasion at the beaches. (Plate No. 59) The Japanese were willing to risk the loss of their entire mobile fleet for the one opportunity of maneuvering their cruisers and battleships to within target range of the troop and supply transports in Leyte Gulf.

The decision to risk their most valuable military asset in an attempt to repel General MacArthur's invasion of Leyte emphasized again the importance which the Japanese attached to the Philippines. Admiral Soemu Toyoda, Commander in Chief of the Combined Fleet, was fully conscious of the hazards involved. "Since without the participation of our Combined Fleet ", he stated, "there was no possibility of the land-based forces in the Philippines having any chance against your forces at all, it was decided to send the whole fleet, taking the gamble. If things went well we might obtain unexpectedly good results; but if the worst should happen, there was a chance that we would lose the entire fleet; but I felt that that chance had to be taken.... Should we lose in the Philippines operations, even though the fleet should be left, the shipping lane to the south would be completely cut off so that the fleet, if it should come back to Japanese waters, could not obtain its fuel

[203]

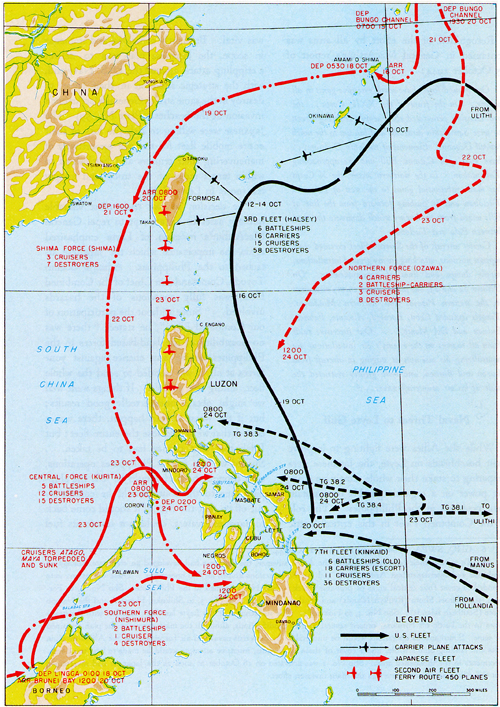

PLATE NO. 59

Approach of Naval Forces

[204]

supply . If it should remain in southern waters, it could not receive supplies of ammunition and arms. There would be no sense in saving the fleet at the expense of the loss of the Philippines."8

Based on similar strategic speculation, the Allied intelligence services assumed that the Japanese would employ the mass of their fleet to defend the Philippines.9 As invasion day approached reconnaissance of every category was intensified to determine the location and movement of the Japanese Navy. It was expected that radio intercepts, aircraft and submarine sightings, and spot reports of A. I. B. agents and guerrilla units in the Philippines would provide the necessary clues on the operations and intent of the Japanese fleet well enough in advance for proper counter measures to be taken.

Long before the actual battle for Leyte Gulf, evidence began to accumulate on the dispositions of the Japanese Navy. As early as 16 October, it was recognized that the heaviest concentration of Japanese fleet units was in the Singapore-Brunei area, that most of the remaining ships were located in Japanese home waters and Formosa and that there were no important naval units in the Philippines.10 The logical conclusion was that if the Japanese used their fleet against General MacArthur's landing forces in the Philippines they would probably converge from these two areas with the stronger elements coming up from the south.

Indications of Japanese Intentions

The Japanese tactical plan was also diagnosed in part during the first week in October. The division of the enemy fleet between the Singa-

[205]

pore-Brunei Bay area and Japan Proper led to the assumption that the enemy naval air strength would probably "cooperate in the East China Sea-Empire Area" and that the "whole remaining surface power" would "operate in the Sulu and South China Seas west of the Philippines." It was significantly recognized, too, that one of the immediate dangers to General MacArthur's amphibious landings in the Philippines lay in a possible sortie by strong Japanese surface craft from Brunei Bay via Surigao Strait.11

As D-day approached, the movements of the Japanese Fleet were kept under the closest surveillance. It was known on 14 October, for example, that a naval force, consisting of Vice Adm. Kiyohide Shima's minor units which were to participate belatedly in the Battle for Leyte Gulf, was to sortie from the Inland Sea at 2400 and that it was to pass through Bungo Channel early the next morning.12 As confirmation of this movement, a U.S. submarine sighted Admiral Shima's force just off Bungo Channel on a southeasterly course at 0800 on 15 October.13 Although Admiral Shima's cruiser and destroyer group was en route to the Formosa area at this time and did not receive definite orders to join the converging forces against Leyte Gulf until 1645 on 23 October, this was the first sighting of any of the units which were to participate in the crucial battle. Admiral Shima's force was sighted again on 16 October by Allied aircraft about 115 miles east of Okinawa,14 and on 18 October by a U. S. submarine approximately 100 miles north of Okinawa.15 The next day Japanese naval supply units were ordered to Bako for the replenishment of Admiral Shima's Force thus suggesting a possible sortie by his group.16 It was subsequently sighted on 2117 and 22 October the latter time about 150 miles northwest of Luzon en route to the Philippines.18

It was also known by 16 October that a force of major units under Vice Adm. Takeo Kurita in the Singapore area was preparing

[206]

for a possible further sortie.19 Two days later it was recognized that this force might penetrate the Central Philippines to attack the United States landing forces. Although it was considered doubtful that "such a hazardous operation would be ordered," it was believed that it would "be detected at an early stage " and that United States supporting forces " with their air strength " would be able " to cope with the maximum estimated naval powers "which the Japanese could bring to bear.20 On 20 October it was further reported that a Japanese "10,000 ton tanker, a repair ship and a coast defense vessel" were en route to Coron Bay in the Calamian Islands for the replenishment of Admiral Kurita's force.21 Although this was the only indication up to that time of a "possible movement of major enemy fleet units to the southwest Philippines," it was a sign that could not be ignored.22

Vice Adm. Jisaburo Ozawa's carrier force was not actually sighted until 1640 on 24 October, but it was correctly estimated two days before that he was at sea as of 20 October23 and "somewhere in the Formosa-P. I. Sea area on 22 October."24 Significant too was the estimate of the same date that he was " moving probably toward the P. I. area in connection with counter measures to be taken against the Allied forces in the P. I. invasion."25 Thus, with the landings on Leyte scarcely underway, a good general picture of Japanese fleet dispositions and probable intentions had been pieced together.

Approach of Enemy Naval Forces

Definite indications that the enemy was approaching the Philippines in force came from sightings of powerful enemy naval units by U. S. picket submarines previously assigned to search the waters off Borneo and Palawan. At 0200 on 22 October three large unidentified warships were reported in Palawan Passage on a northeast course with a speed of 21 knots.26 No further sightings were reported that day in spite of the fact that extensive and prolonged air searches were made. At 0200 on 23 October, however, the submarine Darter sighted " three probable battleships " on approximately the same course. Within two hours the Darter estimated that this task force was composed of at least 9 ships with many radars. At 0930 the submarine Bream sighted more units and launched a torpedo attack obtaining two hits on one cruiser.27

Early the same morning the Darter reported sinking an Atago class cruiser and scoring four hits on another.28 At 0700 the Dace, which had been assigned to cover the western approaches of Balabac Strait estimated that it had probably sunk a Kongo class battleship in a force of 11 ships which included battleships,

[207]

cruisers, destroyers, and a carrier.29 Subsequent investigation determined that the Darter and Dace had sunk the heavy cruisers Atago and Maya and damaged the heavy cruiser Takao.30 Before sunrise on 23 October the first blows of the fateful Battle for Leyte Gulf had been struck, with U.S. submarines performing yeoman service in their running fight with the enemy's large surface units. Not only did the submarines strike the first damaging blows against Admiral Kurita's ships but they alerted all United States forces to the approach of the main Japanese striking force two full days in advance of the final battle.

In the meantime the other Japanese naval forces which were to participate in the Battle for Leyte Gulf had not been sighted in Philippine waters. That Admiral Shima was nearing Coron Bay, however, was clear by 23 October, for he had requested that Japanese supply units be sent there early the morning of 23 October to fuel his force.31 It was a highly probable assumption, too, that Admiral Ozawa's task force was prowling the waters of the Formosa-Philippine Sea area, although he had not yet been located. Later events were to prove this assumption correct. The fourth unit of the Japanese naval forces converging on the Philippines, Vice Adm. Shoji Nishimura's Southern Force, had also not been sighted by midnight of 23 October.

On 24 October, however, the various pieces of the Japanese naval puzzle were gradually pieced together. Early that morning continuous submarine sightings were made of the task force which had been moving through Palawan Passage. By 0030 it was estimated to consist of 15 to 20 ships including three probable battleships.32 A few hours later the submarines Angler and Guitarro reported this force heading south through Mindoro Strait.33 At 0810 U.S. carrier planes operating at a maximum range made a preliminary attack on the Japanese task force. Within the hour carrier search planes also reported that the enemy naval units were "moving northeast into Tablas Strait."34 This force, designated as the Central Force, originally consisted of five fast battleships including the mysterious and dangerous 64,000 ton monsters the Yamato and Musashi, 12

[208]

accompanying cruisers, and 15 destroyers.35

At 0905 of 24 October aircraft sighted a second enemy fleet off Cagayan Islands well into the Sulu Sea on a course which indicated an intent to enter the Mindanao Sea. Aerial attacks were launched almost immediately with both bomb and rocket hits claimed on several of the Japanese units.36 This Southern Force, under Admiral Nishimura, although not as large as the previously located Central Force, showed enough strength in battleships and cruisers to identify it as a major task formation.37 It had left Brunei Bay on 22 October and at about noon of the 23rd passed through Balabac Strait and into the Sulu Sea. In the meantime Admiral Shima had departed from Coron Bay at 0400 on 24 October and sailed southward. After rounding the Cagayan Islands, his small force of 3 cruisers and 4 destroyers turned eastward where it was sighted west of Negros about noon. Admiral Shima followed Admiral Nishimura's Southern Force some 40 to 50 miles astern through the Mindanao Sea toward Leyte Gulf.

With the sighting of the Southern Force, the form of the Japanese plan began to take shape. The Central Force, under Admiral Kurita, would pass through the Sibuyan Sea, emerge from San Bernardino Strait and then set a course southward for Leyte Gulf. Mean while, the Southern Force, under Admiral Nishimura, would pace its approach via the Mindanao Sea and Surigao Strait so that both fleets, in a co-ordinated pincer movement, would converge simultaneously on the Allied flanks and attack the vulnerable "soft shipping" busy unloading in Leyte Gulf.38 (Plate No. 60)

From the number and types of enemy warships moving through Philippine waters it was apparent to General MacArthur's staff that the Japanese were launched upon a full-scale operation to destroy or at least seriously upset the invasion. That they would not employ their carriers in such an ambitious plan was unthinkable and yet the Japanese carriers had not been sighted. It could only be concluded that the

[209]

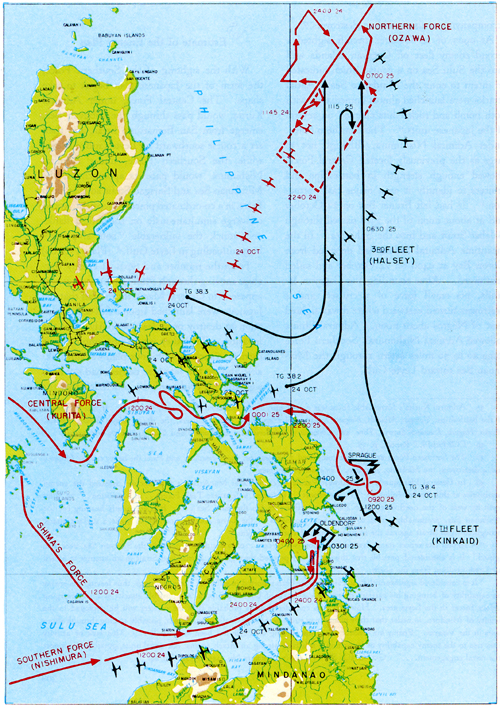

PLATE NO. 60

Battle for Leyte Gulf

[210]

missing carriers constituted still another force not yet located, probably Admiral Ozawa's force previously estimated to be somewhere in the Formosa-Philippine Sea area. This opinion was strengthened on the morning of the 24th when some 200 enemy planes launched a series of attacks concentrated mainly upon the carriers of the Third Fleet.39 It was noticed that a great proportion of the attacking fighter planes consisted of carrier types. This fact, together with the direction of their approach, led Admiral Halsey to intensify his search to the north and east for some sign of enemy carriers.

In the crucible of the coming battle, General MacArthur's position was unique. The sweep of his forces along New Guinea had been consistently directed so that each operation would have available the full protection of his own land-based air force. Every advance had been predicated on the basic plan of procuring air bases 200 to 300 miles apart from which successive tactical advances could be made under a guaranteed air umbrella. By invading Leyte two months in advance of the original schedule, however, General MacArthur was compelled to send his troops into a landing area without his own controlled air coverage. The U. S. Navy therefore had a double responsibility. Initially, it had to assist the landing itself by its usual tasks of shore bombardment, convoy escort, and plane cover. In addition, it had the important mission of giving General MacArthur further air support for a period of time beyond the landing date until he could develop local airfields and stage his own air units forward from the south.

At Leyte General MacArthur was completely dependent on forces not under his control to protect his landing operation. Should the naval covering forces allow either of the powerful advancing Japanese thrusts to penetrate into Leyte Gulf , the whole Philippine invasion would be placed in the gravest jeopardy. It was imperative, therefore, that every approach to the Gulf be adequately guarded at all times and that an enemy debouchment via Surigao and. San Bernardino Straits be blocked with adequate Allied naval strength.40

The naval forces protecting the Leyte invasion were disposed in two main bodies. The Seventh Fleet, under Admiral Kinkaid, protected the southern and western entrances to Leyte Gulf while the stronger Third Fleet, under Admiral Halsey operated off Samar to cover San Bernardino Strait and approaches from the north and east. Admiral Halsey's immediate superior was Admiral Nimitz in Hawaii; Admiral Kinkaid was responsible to General MacArthur. While it was realized that such a division of command entailed certain disadvantages, it was theoretically assumed that frequent consultation and co-operative liaison would overcome any difficulties in the way of proper co-ordination. The coming battle was to demonstrate the dangers involved in the lack of a unified command and the misunderstandings that can ensue during major operations in which the commander ultimately responsible does not have full control over all forces in the operation.

As Admiral Kurita's Central Force threaded its way through the narrow, reef-filled waters of

[211]

the Sibuyan Sea during the morning and afternoon of the 24th, it was kept under repeated and severe attack by planes of the U. S. Third Fleet. The Musashi, one of the newest and largest of Japan's battleships which mounted 18-inch guns, was sunk; its sister ship, the mighty Yamato, was hit; a heavy cruiser was crippled; other cruisers and destroyers were damaged. The increasing force of these aerial blows together with the torpedoes of Seventh Fleet submarines caused Admiral Kurita, who was operating without air cover, to reverse his course for a time in order to take stock of the situation and reform his forces. This temporary withdrawal executed at 1530 was later reported by overly optimistic Allied pilots as a possible retirement of the Japanese Central Force. Admiral Kurita had no intention of abandoning his mission, however, and at 1714 he headed once more for San Bernardino Strait. Shortly thereafter he received a message from Admiral Toyoda in Tokyo: "All forces will dash to the attack, trusting in divine assistance."

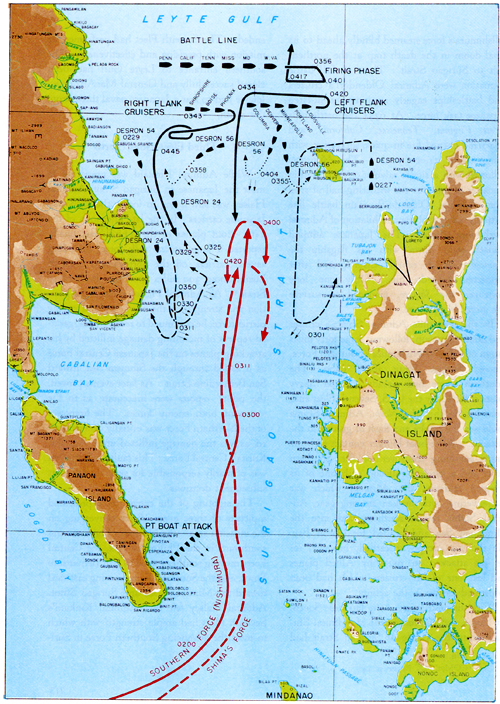

In the meantime, Admiral Nishimura's Southern Force sailed doggedly on into the Mindanao Sea and passed Bohol despite the fact that it had been sighted and attacked off Cagayan Island.41 Amply forewarned by sightings, Admiral Kinkaid had dispatched almost the whole of the Seventh Fleet's gunnery and torpedo force under Rear Adm. Jesse B. Oldendorf, to intercept and destroy the approaching Japanese warships.42 Admiral Oldendorf took full advantage of both the geography of the battle area and his foreknowledge of the enemy's route of advance. PT squadrons were deployed at the entrance to Surigao Strait at a place where the Japanese would have to reform in column to negotiate the narrow passage. Behind the torpedo boats, covering the northern part of the strait, were posted the destroyer squadrons, cruisers, and battleships to form the horizontal bar to a "T" of vast fire power which the enemy would be forced to approach vertically as he moved forward. (Plate No. 61)

The ambush worked perfectly. As Admiral Nishimura's forces pushed forward through the smooth waters of Surigao Strait in the early hours of 25 October the PT boats, waiting in the darkness near Panaon Island, launched their torpedoes. Results were not clear but some damage was inflicted.43 Three separate, co-ordinated attacks by U. S. Destroyer Squadrons 54, 24 and 56 followed in rapid succession as torpedo after torpedo found its mark. Destroyer Squadron 54 operating near Cabugan Grande Island and Hibuson Island launched its spread of torpedoes about 0300. A few minutes later, at 0327, Destroyer Squadron 24 fired its swift and deadly missiles from 700 yards off the port bow of the enemy formation. The third and final torpedo attack was made by Destroyer Squadron 56. At 0337 Admiral Oldendorf issued the order: "Launch attack-get the big boys."44 Admiral Nishimura's force was not only confused and slowed by the tempest of torpedoes, it was mortally crippled. Virtually every unit in the formation was either sunk or badly damaged.

Despite this severe punishment, Admiral

[212]

Nishimura's force steamed blindly ahead to its final doom in the death trap at the northern exit to Surigao Strait. There in full battle formation were Admiral Oldendorf's cruisers and battleships eagerly awaiting the ill-fated Japanese task force. At 0354 the battleships West Virginia, Tennessee, California, and Maryland opened fire in quick succession with range about 21,000 yards. The Mississippi followed with a single salvo at 0411.45 Within a matter of minutes the withering hail of steel from Admiral Oldendorf's main battle line virtually completed the annihilation of Admiral Nishimura's force. The Japanese admiral himself went down with his flagship the Yamashiro which rapidly disintegrated after numerous torpedo hits. Only one lone destroyer, the Shigure, managed to survive the incredible carnage.

In the meantime Admiral Shima's cruiser and destroyer group, following some forty miles astern of Admiral Nishimura's Southern Force, entered Surigao Strait about 0300. The Southern Force had already suffered heavy losses inflicted by the U. S. Seventh Fleet and, from his flagship the Nachi, Admiral Shima could see the smoke and flash of gunfire in the distance. After brief blinker contact with the single surviving destroyer of the Southern Force and a careless collision with one of its crippled cruisers, the Mogami, which was maneuvering with broken steering gear, Admiral Shima retired southeastward into the Mindanao Sea and headed for Coron Bay. He did not escape unscathed, however, for he was attacked en route by Allied planes and lost one of his cruisers which had been torpedoed earlier in the action.

With the destruction of the Japanese Southern Force and the retirement of Admiral Shima's units, the Battle of Surigao Strait had ended. The Seventh Fleet had performed its mission with precision and effectiveness. The southern entrance to Leyte Gulf had been closed successfully and General MacArthur no longer had to fear a Japanese naval threat from the south.

While Admiral Kinkaid was preparing to meet the Japanese in Surigao Strait, Admiral Halsey was still trying to locate the suspected Japanese carriers. In the late afternoon of the 24th, scout planes of the Third Fleet finally reported a large enemy task force, including several carriers, off the northeastern coast of Luzon about 300 miles from San Bernardino Strait.46 As Admiral Halsey plotted the position and strength of the newly sighted enemy carrier force, he continued to received exaggerated reports of mounting damage inflicted by his attacking planes on the Japanese Central Force as it sailed through the Sibuyan Sea, toward San Bernardino Strait. As later events proved, the pilots' reports were inaccurate as to the status of both enemy forces. The firepower of the Northern Force was initially overestimated as was the damage inflicted upon Admiral Kurita's Central Force. This faulty information was primarily responsible for several important subsequent decisions.

The sighting of the carrier force presented a picture of three enemy fleets converging on the invasion area-the Northern Force moving southward in the Philippine Sea, the Central Force moving southeastward to San Bernardino Strait, and the Southern Force moving eastward toward the Mindanao Sea and Surigao Strait. Admiral Halsey felt that Admiral Kinkaid's Seventh Fleet had ample strength with which to meet the advancing Southern Force in Suri-

[213]

PLATE NO. 61

Battle of Surigao Strait

[214]

gao Strait . He judged from his aviators' optimistic reports that the Central Force had been greatly damaged, had perhaps retired, and in all likelihood had been removed as a serious menace. He reasoned that, in any event, its strength had been reduced to the point where any threat it presented would be satisfactorily overcome by Admiral Kinkaid's Seventh Fleet. He estimated that the Northern Force comprised the whole carrier strength of the Japanese and therefore constituted the most potent danger to be met.47 Influenced by these factors, Admiral Halsey decided to move his entire force northward as a unit and intercept the Japanese carriers.

During the afternoon of 24 October, however, Admiral Halsey had organized Task Force 34 as a strong surface force comprising the battleships Iowa, New Jersey, Washington, and Alabama, 2 heavy cruisers, 3 light cruisers, and 14 destroyers.48 According to Admiral Halsey, the dispatch forming Task Force 34 was not an executive dispatch but a tentative battle order and was so marked.49 As everyone was greatly concerned about the Japanese Central Force, including Admiral Halsey who knew its position and formidable fire power, it was assumed that Task Force 34 would engage Admiral Kurita's force which was heading east through the Sibuyan Sea. In the early evening Admiral Halsey informed Admiral Kinkaid and others of the position of the Japanese Central Force and added that he was " proceeding north with three groups to attack the enemy carrier forces at dawn."50 Accordingly, on the evening of the 24th, he withdrew the battleships, carriers, and supporting ships of the Third Fleet from San Bernardino Strait. It was a crucial decision and no end of confusion and uncertainty followed his action. As the fast battleships of the Third Fleet had been detached from the carrier groups and organized as Task Force 34, it was assumed that Task Force 34 was still guarding San Bernardino Strait . Although no definite statement had been made to this effect by Admiral Halsey,51 Admiral Kinkaid thought that the big battleships were standing by awaiting the Japanese Central Force and that Admiral Halsey was going after the Japanese Northern Force with carrier units. Actually, however, Admiral Halsey took his three complete task groups on his run to the north and left San Bernardino Strait open.52

[215]

Free passage through San Bernardino Strait was a pivotal point of the enemy's strategy in his daring scheme to strike the Allies in Leyte Gulf . Admiral Halsey did not know that Japan 's carriers were to be deliberately sacrificed in a bold gamble to keep the Philippines from falling to the Allies. It was afterward revealed that the Northern Force under Admiral Ozawa, almost completely destitute of planes and pilots, had only one mission-to serve as a decoy and lure the most powerful units of the U. S. Fleet away from the Leyte area.53 It was expected that the Northern Force would probably be destroyed, but it was hoped that this desperate device would enable the Japanese Central Force to pass unmolested through San Bernardino Strait and move southward into Leyte Gulf, timing its approach to coincide with the arrival of the Southern Force from Surigao Strait.

To accomplish his mission, Admiral Ozawa continually sent out radio messages in an effort to advertise his position to the U. S. Fleet. An undetected fault in his transmission system, however, prevented the Third Fleet from intercepting these signals. Equally important to later operations, communication difficulties and divided responsibility also prevented an adequate exchange of information between the enemy's Northern and Central Forces.

As the U.S. Third Fleet sought contact with the carriers of the Northern Force during the evening of the 24th, Admiral Kurita in a remarkable feat of high-speed navigation, skillfully led his warships through the darkness southeastward into the treacherous passes of the Sibuyan Sea. Since he had received no message from Admiral Ozawa off Luzon, he was actually unaware that the main body of the U.S. Fleet had been drawn away from the mouth of San Bernardino Strait. Nevertheless, Admiral Kurita in compliance with repeated orders from the Combined Fleet, continued on his original task, setting his course for Leyte Gulf. By midnight he was in the waters of San Bernardino Strait and at approximately 0035 of 25 October he debouched into the Philippine Sea. About 0530, as he was coming down the coast of Samar, Admiral Kurita received word of the loss of Admiral Nishimura's two battleships and of the damage to the cruiser Mogami. Although he was unaware of the fact, his was now the only Japanese force within striking distance of Leyte. The task of destroying the U.S. invasion units rested solely in his hands.

At dawn on 25 October, three groups of escort carriers under Admiral Thomas L. Sprague were disposed east of Samar and Leyte Gulf. The Northern CVE Group with 6 carriers, 3 destroyers, and 4 destroyer escorts was under the command of Rear Adm. Clifton A. F. Sprague.54 It was on a northerly course about fifty miles east of Samar and approximately half way up the east coast of the island, directly in the path of Admiral Kurita's oncoming force.

[216]

Some twenty or thirty miles east southeast was the Middle CVE Group with the same composition under Rear Adm. Felix B. Stump.55 Farther to the south off northern Mindanao was the Southern CVE Group consisting of 4 carriers, 3 destroyers, and 4 destroyer escorts.56 This group was under the direct supervision of the over-all escort carrier commander, Admiral Thomas Sprague.

Through a series of fatal misunderstandings directly attributable to divided command, ambiguous messages, and poor communication between the U.S. Third and Seventh Fleets, neither Admiral Kinkaid at Leyte Gulf, nor Admiral Sprague off Samar, realized that the exit from San Bernardino Strait had been left unguarded. They had no reason to expect such a situation; previous commitments were firm. During the night of the 24th, however, Admiral Kinkaid became uneasy concerning the actual situation at San Bernardino Strait and decided to check on the position of Task Force 34. At 0412 on the 25th Admiral Kinkaid sent an urgent priority dispatch (241912) telling Admiral Halsey of the results in Surigao Strait and asking him the vital question: "Is TF 34 guarding San Bernardino Strait."57 The reply to Admiral Kinkaid's dispatch was not sent until 0704, by which time the first salvos of Admiral Kurita's battleships were reverberating across the waters off Samar. Admiral Halsey's answer said: "Your 241912 negative. Task Force 34 is with carrier group now engaging enemy carrier force."58

It was a dramatic situation fraught with disaster. The forthcoming battle between the U.S. Seventh Fleet's slow and vulnerable " jeep" carriers and the Japanese Central Force of greatly superior speed and fire power gave every promise of a completely unequal struggle. The light carriers of Admiral Sprague were no match for the giant battleships and heavy cruisers of the Japanese Central Force. Should the enemy gain entrance to Leyte Gulf , his powerful naval guns could pulverize any of the eggshell transports still present in the area and destroy vitally needed supplies on the beachhead. The thousands of U. S. troops already ashore would be isolated and pinned down helplessly between enemy fire from ground and sea. Then, too, the schedule for supply reinforcement would not only be completely upset, but the success of the invasion itself would be placed in grave jeopardy. The battleships and cruisers of the Seventh Fleet were over 100 miles away in Surigao Strait with their stock of armor-piercing ammunition virtually exhausted by the pre-landing shore bombardment and the decisive early morning battle with the Japanese Southern Force. Admiral Halsey's Third Fleet was almost 300 miles away still in hot pursuit of the Northern Force and could not possibly return in time to halt the progress of Admiral Kurita.

On shore, General MacArthur had been powerless to do more than point out the absolute need for constant carrier air cover over the Leyte beaches. Under the divided command set-up, he had no effective control over the Third Fleet. Having advanced beyond the range of his own land-based aircraft, he was completely dependent upon carrier planes for

[217]

protection-a fact which he had emphatically made clear both before and during the planning for the invasion. On 21 October he had reiterated his conception of Admiral Halsey's mission saying:

The basic plan for this operation in which for the first time I have moved beyond my own land-based air cover was predicated upon full support by the Third Fleet; such cover is being expedited by every possible measure, but until accomplished our mass of shipping is subject to enemy air and surface raiding during this critical period; . . . consider your mission to cover this operation is essential and Paramount .... 59

Now General MacArthur could do nothing but consolidate his troops, tighten his lines, and await the outcome of the impending naval battle.

Although Admiral Kurita's Central Force had suffered considerable damage in its course across the Sibuyan Sea, it was still a formidable fleet when it broke through San Bernardino Strait and headed for Leyte Gulf. The main force consisted of the mighty Yamato and three other fast battleships, the Kongo, Haruna, and Nagato. These were supported by the six heavy cruisers Chikuma, Haguro, Chokai, Tone, Kumano, and Suzuya. The two light cruisers Yahagi and Noshiro and eleven destroyers completed Admiral Kurita's fast and powerful task force. In quest of big game, its guns and shell hoists were loaded down with armor-piercing projectiles as it steamed southward along the coast of Samar.

First indication that the enemy might be approaching came at 0637 when the escort carrier Fanshaw Bay intercepted Japanese conversation on the interfighter director net. This was followed closely by sighting of antiaircraft bursts to the northwest about twenty miles distant. The final shock came at 0647 when a pilot aboard a plane from the Kadashan Bay frantically announced that a large enemy surface force of battleships, cruisers, and destroyers was closing in about twenty miles to the northwest at a speed of 30 knots. The frightful possibility had materialized; the Japanese Central Force had broken through San Bernardino Strait.

Admiral Kurita had located the U. S. escort carrier force at 0644 and a few minutes later at 0658 he gave the order to join battle. The Yamato's 18-inch guns fired first with the cruisers following as soon as they came within range. Never before had U. S. warships been subjected to such heavy caliber fire. With the world's biggest guns blazing away, Admiral Kurita pressed the attack at full speed. (Plate No. 62)

As soon as the enemy was sighted the Northern CVE Group changed course to 090°, due east, and began launching all available aircraft. Scarcely had the planes been sent aloft when large caliber shells began falling among the units of the formation. Admiral Kurita was closing rapidly, straddling the U.S. escort carriers with dye-marked salvos that landed with uncomfortable accuracy and bracketed their targets with red, yellow, green, and blue splashes. The situation was most critical and from this point on it was only a question of how to save the greatly outnumbered and outgunned U. S. ships from almost certain destruction.

At 0701 the commander of the Northern

[218]

PLATE NO. 62

Battle off Samar

[219]

CVE Group reported the alarming news that he was in contact with the enemy and urgently needed assistance. He then ordered a general retirement to the southwest in the hope of obtaining support from the heavy forces in Leyte Gulf. Admiral Kinkaid received the request for support at 0724 and promptly ordered Admiral Oldendorf "to prepare to rendezvous his forces at the eastern end of Leyte Gulf"; the escort carrier planes were sent the same order, and a dispatch was transmitted to Admiral Halsey requesting immediate aid.60

Admiral Kurita pushed the attack vigorously. His ships gradually closed and continued to send a steady avalanche of shells at the escort carriers. Huge geysers of water erupted around Admiral Sprague's units as the big Japanese batteries began to find the range. As the battle developed, Admiral Kurita, intent on encircling the retiring U. S. ships, deployed several of his cruisers on the left flank from where they delivered the most troublesome fire of the battle. Several destroyers were also deployed on the right flank while the rest of his force pressed the attack from astern. Along with these surface attacks Japanese air units based in the Philippines launched a series of Kamikaze strikes against the U. S. carriers. In his great distress Admiral Kinkaid sent Admiral Halsey another dispatch: "Urgently need fast BB's Leyte Gulf at once."61 Admiral Halsey responded to the Seventh Fleet's appeal by ordering Vice Adm. John S. McCain, Commander of Task Group 38.1, which had been refueling to the east, to attack the enemy at San Bernardino as soon as possible.62 Meanwhile the Third Fleet continued to steam northward in hot pursuit of the Japanese carrier group.

Admiral Sprague's escort carriers used every trick of sea fighting to escape the heavy fire of the Japanese Fleet and to inflict losses on the enemy. Evasive tactics were ordered; thick smoke screens were laid down; temporary refuge was sought in a providential rain squall. In a desperate effort to stem the enemy advance, the destroyers and destroyer escorts fought back furiously. Interposing themselves between the carriers and their adversary, they boldly closed the range and fired their five-inch guns and torpedoes at cruiser and battleship targets. Both the Johnston and the Heermann challenged the Kongo. The escort carriers also engaged with gunfire whatever units of the enemy came within range. At the same time their planes attacked the enemy continuously and succeeded in putting several of his cruiser units out of action. They were greatly handicapped, however, by the damage inflicted on the carriers. The pilots, seeing their carrier decks ripped open or their ships sunk, made forced landings on the already overcrowded airstrip at Tacloban. Some also landed on the Dulag strip while others were compelled at the last minute to ditch their planes in Leyte Gulf.

As the battle progressed the situation became more desperate for the U. S. units. With disaster staring him in the face, Admiral Kinkaid sent Admiral Halsey another urgent dispatch which the latter received at 0900 "Our CVE's being attacked by 4 BB's 8 cruisers plus others. Request Lee cover Leyte at top speed. Request fast carriers make immediate strike."63 By this time ammunition aboard the escort carriers was running low; some of the destroyers had expended their torpedoes and the torpedo planes were reduced to the dire expedient of making dummy runs on the

[220]

enemy ships. Both the screening force and the carriers sustained considerable damage. The Gambier Bay was hit hard and sank at 0911 with an enemy cruiser pumping shells into her at a range of less than 2,000 yards. The destroyer Johnston, which had been under continuous heavy fire, was fatally struck and had to be abandoned. She rolled over and sank at 1010. The destroyer Hoel and the destroyer escort Roberts were also sunk. Early damage was also inflicted on the escort carriers Santee, Suwannee, and Sangamon. At 0922 Admiral Halsey had received a dispatch sent by Admiral Kinkaid at 0725: "Under attack by cruisers and battleships ... request immediate air strikes. Also request support by heavy ships. My OBB's low in ammunition."64

Meanwhile, off Samar, victory lay within Admiral Kurita's grasp. After almost two and one-half hours of continuous battle the flanking enemy units began closing in, firing salvo after salvo at the escort carriers dodging desperately to avoid more damage. By 0920 the heavy cruiser Tone was within 10,000 yards of her targets and on the starboard flank the Japanese 10th Destroyer Squadron pressed the attack with torpedoes. The situation had become virtually hopeless for Admiral Sprague's task group, and few expected to come out of the ordeal afloat. Once more Admiral Kinkaid sent an insistent plea to Admiral Halsey, this time in the clear: "Where is Lee? Send Lee."65 Almost simultaneously Admiral Halsey received an urgent dispatch from Admiral Nimitz in Pearl Harbor: "The whole world wants to know where is Task Force 34."66

Admiral Kurita Breaks Off Engagement

Then, as if in answer to fervent prayer, the unexpected happened. Admiral Kurita broke off the engagement.67 His units had sustained no little damage,68 and like everyone else he was unaware of the true battle situation. He

[221]

therefore ordered his forces to cease firing and reassemble to the north. For the U.S. carrier forces this retirement by the enemy meant a remarkable and completely unexpected escape. Admiral Sprague in summing up the results of the battle shortly thereafter stated:

... the failure of the enemy main body and encircling light forces to completely wipe out all vessels of this Task Unit can be attributed to our successful smoke screen, our torpedo counter-attack, continuous harassment of the enemy by bomb, torpedo, and strafing air attacks, timely maneuvers, and the definite partiality of Almighty God.69

The continuous and urgent dispatches from Admiral Kinkaid and the cryptic message from Admiral Nimitz finally led Admiral Halsey to change course and direct the bulk of his fleet southward toward Leyte. He accordingly directed Task Force 34 under Admiral Lee and Task Group 38.2 under Rear Adm. Gerald F. Bogan to proceed south toward San Bernardino Strait. At exactly 1115, when he was expecting the pagoda masts of Admiral Ozawa's force to appear over the horizon at any minute he made the crucial decision to return to Leyte Gulf. He expected to arrive early the next morning.

The other units of the Third Fleet, Admiral Mitscher's Task Force 38 with Task Group 38.3 under Admiral Sherman and Task Group 38.4 under Admiral Davidson were to continue against the enemy carrier force. Throughout the afternoon of 25 October Third Fleet carrier planes struck Admiral Ozawa's force again and again. When the battle was over the Japanese had lost the famous carrier Zuikaku and the three light carriers Chitose, Chiyoda, and Zuiho. One light cruiser and two destroyers were also sunk, but the two hermaphrodite battleship-carriers Ise and Hyuga escaped with minor damage. United States forces suffered no surface losses in the engagement.

After regrouping his forces and evaluating the situation, Admiral Kurita decided to make one last attempt against Leyte Gulf. At 1120 he ordered his ships to change course toward the target area to the southwest. He was en route approximately one hour, however, and only 45 miles from his objective when he finally decided to give up the attempt. At 1236 he ordered his ships about. As he retraced his course to the northwest his force came under attack by planes from the Seventh and Third Fleets. Although he had sustained considerable damage, Admiral Kurita managed to limp through San Bernardino Strait at 2130 on 25 October. Of his original force of 32 ships he escaped with 4 battleships, 4 cruisers and 7 destroyers. In the meantime Admiral Halsey came racing down from the north with his big battleships. They were not to fire a shot, however, for when they arrived it was too late. Admiral Kurita had escaped.

In an evaluation of the battle, Admiral Sprague's humble recognition of divine intervention must be read in conjunction with Admiral Halsey's radio dispatched on the day of impending disaster:

To prevent any misunderstanding concerning recent Third Fleet operations, I inform you as follows: It became vital on 23 October to obtain information of Japanese plans, so 3 carrier groups were moved to the Philippine coast off Polillo, San Bernardino and Surigao to search as far west as possible; on 24 October Third Fleet air struck at Japanese forces moving east through the Sibuyan and Sulu Seas; apparently the enemy planned a co-ordinated attack, but their objective was not ascertained and no carrier force located until afternoon of 24 October; merely

[222]

to guard San Bernardino Strait while the enemy was co-ordinating his surface and carrier air force would be time wasted, so 3 carrier groups were concentrated and moved north for a surprise dawn attack on the carrier fleet; estimated the enemy force in the Sibuyan Sea too damaged to threaten Com7thFlt, a deduction proved correct by events of 25 October off Surigao; the enemy carrier force caught off guard, offering no air opposition over the target or against our force; evidently their air groups were land-based, arriving too late to fight; I had projected surface strike units ahead of our carriers in order to coordinate surface and air attacks against the enemy; Com7thFlt sent urgent appeal for assistance just when my overwhelming force was within 45 miles of the crippled enemy; no alternative but to head south in response to call, although 1 was convinced his opponents were badly damaged from our attack of 24 October, a conviction later justified by events off Leyte....70

The command decisions during the Battle for Leyte Gulf require a realistic appraisal. The "events off Leyte" were the free entry of Admiral Kurita's Force into the Leyte area to a point where the complete destruction of the U. S. transports and escort carriers was an immediate and frightful possibility. Except for the superb and sacrificial intervention of a covering force under Admiral Sprague, the brilliant operation of Admiral Oldendorf in Surigao Strait, and the fortunate decision of Admiral Kurita, the results of the battle would have been different.

During the course of these critical naval operations, the Japanese air forces had intensified their attacks both on sea and shore. The Seventh Fleet was busily occupied in a struggle for survival, employing its air strength to fight off hordes of hostile planes attacking in co-ordination with enemy fleet units. Its problem was further complicated by the appearance of Kamikaze pilots whose novel suicide tactics initially caused considerable havoc.

On land, General MacArthur's troops without adequate air cover were exposed to continuous and damaging raids by enemy planes. Bombing and strafing from tree-top levels interfered with the unloading of supplies and hampered the progress of the advance into Leyte. In addition, under cover of their naval operations the Japanese had succeeded in landing 2,000 troop reinforcements from Cagayan at Ormoc on 25 October.71

The Japanese admirals had played for high stakes and lost. Their plan missed success, however, by only a slim margin. Had the Central Force adhered to its mission and proceeded into Leyte Gulf, the American invasion would in all probability have experienced a setback of incalculable proportions. The enemy's heavy guns would have experienced little trouble in pounding the remaining transports and landing craft. Shore positions and troop installations could have been bombarded almost at leisure and Admiral Kurita could then have continued on toward Surigao Strait. At this stage of the game, the weakened escort carriers and the ammunition-depleted battleships of the Seventh Fleet could have offered only relatively minor opposition. The intervention of the Third Fleet was too far removed to cause immediate tactical concern.

Within the narrow limits of a lost opportunity, the Japanese Navy, however, had suffered a crushing and fatal defeat.72 The enemy fleet as an integral unit was no longer to be reckoned as a major factor in future operations, and his

[223]

carrier force especially was now known to be impotent. The greatest sea battle in history left the remaining units of the Japanese Navy increasingly vulnerable to future Allied naval and air strikes. Against the background of this decisive naval victory, the strong wedge of General MacArthur's ground forces was driven solidly into the vulnerable Japanese flank on Leyte. If he could establish his forces securely in the central Philippines, the Japanese would be powerless to prevent him from overrunning the rest of the archipelago and bisecting the Japanese Empire.

In recognition of the overwhelming naval victory, General MacArthur sent the following message of appreciation to Admiral Nimitz:

At this time I wish to express to you and to all elements of your fine command my deep appreciation of the splendid service they have rendered in the recent Leyte operations. Their record needs no amplification from me but I cannot refrain from expressing the admiration everyone here feels for their magnificent conduct. All of your elements-ground, naval and air-have alike covered themselves with glory. We could not have gone along without them. To you my special thanks for your sympathetic and understanding cooperation.73

Japanese Reaction to the Invasion

The decisive defeat of the enemy fleet in the waters of the Philippines meant the failure of only one phase of Japan's threefold plan for disrupting the Allied invasion of Leyte. Despite the loss of the naval battle, Japanese efforts in the air and on the ground were intensified rather than diminished. By bringing in plane reinforcements from Formosa and Kyushu to numerous existing bases in Luzon, they were able to maintain a continuous aerial offensive against the Allied transports and fleet units in Leyte Gulf throughout the landing period.

Vigorous enemy air assaults began in the afternoon of 24 October with numerous low-level attacks upon Allied beachhead installations. During the next few days, a sustained series of heavy raids by 150-250 planes was directed against escort carrier forces and other surface units. Headquarters of the Sixth Army and General MacArthur's command post in Tacloban did not escape attack. Direct hits were scored within a block of General MacArthur's billet and the Headquarters Company was struck on Thanksgiving Day.

These raids marked the first appearance of the suicidal Kamikaze attack pilot, whose startling debut caused considerable consternation to Allied naval commanders and inflicted widespread destruction on U.S. fleet units in the Leyte area. On 29 October a suicide plane crashed into the Third Fleet carrier Intrepid. The next day, the carriers Franklin and Belleau Wood were struck, resulting in severe damage and loss of personnel. On 1 November the Seventh Fleet lost one destroyer to Kamikaze planes and suffered serious hits on five others. Four days later, the Lexington's signal bridge was blasted by a suicide plane. The necessity of dealing with the dangerous threat of these Kamikaze attacks forced the carriers to commit their planes to their own protection at the expense of furnishing support to the Leyte ground forces.

Allied efforts to counter these suicide attacks and to cover the advancing ground troops were hampered by a delay in construction of suitable airfields on Leyte. Heavy monsoon rains and difficult terrain had disrupted the schedule for development of the vital American air base at Tacloban. The Japanese naturally realized the importance of Tacloban and attacked the air-strip continuously, causing severe destruction to its closely parked planes and incomplete installations and seriously impeding its development.

[224]

One of these raids was particularly successful, destroying twenty-seven planes on the ground. The reckless Japanese pilots sometimes followed American flight formations into the landing areas. The explosion of ammunition dumps or oil storage tanks became an almost nightly occurrence. Except for the vicious air bombardment of Corregidor, at the outbreak of the war, never before in the Pacific had the Japanese blanketed an Allied position with such powerful, sustained, and effective air action.74

The land phase of the enemy's co-ordinated attack plan was also comparatively unaffected by the outcome of the naval battle. Taking full advantage of the temporary insecurity of the American air position, the Japanese poured a steady stream of reinforcements into Leyte from Luzon and the neighboring islands. The 2,000 troops which had been landed at Ormoc on 26 October were followed by other convoys of fresh forces. Additional units of the Japanese 30th and 102nd Divisions were sent from the Visayas and Mindanao and landed during the closing days of October. A first-class veteran outfit, the 1st Division, en route from Manchuria to Luzon, was diverted to Leyte and after disembarking successfully on 1 November was immediately committed to the defense of the Ormoc Corridor. At the same time elements of the 26th Division arrived to swell the total of Japanese troops on the island. These reinforcements made it clear that the enemy intended to hold Leyte at all costs and expected to fight for the Philippines in earnest.

The decision to make a major stand on Leyte was a modification of Japan's original plan to defend the Philippines. Prior to the Allied invasion it had been decided that the main ground battle would be fought on Luzon and that only delaying tactics would be employed in the southern Philippines and in the Leyte area.75 This plan, it was hoped, would give the

[225]

Japanese time to strengthen their forces on Luzon and thereby put them in a position to repel or at least greatly delay General MacArthur's conquest of the entire Philippines.

Several factors, however, influenced the Japanese High Command to alter the initial plan and to order that a decisive stand be made on Leyte. The mistakenly optimistic reports on the losses of the U. S. Third Fleet in the battle off Formosa and the consequent supposed weakness of the U.S. carrier fleet led to a belief that the Japanese land-based air forces could win control of the skies over the Leyte beachhead. It was also thought, in view of the fact that the U. S. landings came so soon after the Morotai operation and the Formosa battle, that General MacArthur might be committing his forces without full preparation or adequate protection. In addition, it was feared that should the Allies gain air bases on Leyte, any defense of Luzon would be made immeasurably more difficult. Therefore Imperial General Headquarters and Field Marshal Terauchi, in overall command of the Japanese Southern Army, felt that Leyte provided an excellent opportunity for a concerted effort by their combined air, naval, and ground forces to defeat and destroy the American invasion troops.

General Yamashita, in direct command of the Japanese ground forces in the Philippines, was opposed to this alteration of the original plan and was reluctant to pour his troops into Leyte for hasty deployment on an unprepared front at the expense of his Luzon defenses.76 Large-scale U.S. carrier raids against the Philippines on the 17th, 18th, and 19th of October had convinced him that the U. S. naval forces were still extremely powerful and were evidently well prepared to cover any Allied invasion. Despite his objections, however, General Yamashita was ordered to dispatch reinforcements immediately and "annihilate the enemy invading Leyte." In accordance with these direct orders, he scrapped his original plan which called for delaying tactics on Leyte and commanded that "the Japanese will fight the decisive battle of the Philippines on Leyte." Despite numerous and damaging Allied attacks on the Leyte convoys, he had succeeded by early November in moving at least 25,000 additional troops and service elements into western Leyte to augment the original defense force.

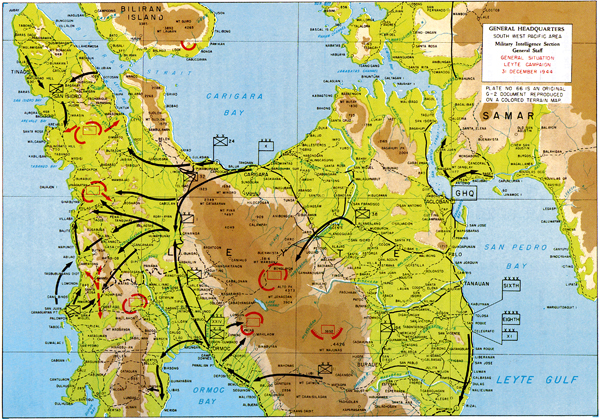

While the Japanese were disembarking their reinforcements and maneuvering into position for a counterattack, General MacArthur's troops continued to drive inland and along the coast in a two-pronged attack and envelopment.77 (Plate No. 63) Except for isolated strong points, such as Catmon Hill behind the XXIV Corps beachhead, only minor opposition was encountered, although enemy resistance was now more determined. By the end of October the XXIV Corps had secured a rough square bounded by Tanauan and Dulag on the coast and Dagami and Burauen, about 10 miles inland, at the western edge of Leyte Valley. Elements of the 7th Division moved south along the coast on Highway No. 1 toward Abuyog, eastern

[226]

PLATE NO. 63

Leyte Attack Continues, 25 October-2 November 1944

[227]

terminus of a fairly good road running completely across Leyte from the Gulf to Baybay on the Camotes Sea. Other elements of this division, together with units from the 96th, established and maintained contact near Dagami. Stiffening enemy resistance was met west of the road from Dagami to Burauen, about eight miles to the south. The 96th Division established and maintained contact with the X Corps to the north.

In the zone of the X Corps the 24th Division, after securing Hill 522, moved west through Leyte Valley along Highway No. 2. Jaro, approximately 15 miles inland from Palo, was reached on 29 October in the face of stubborn resistance by the enemy intrenched in the hills and ridges along the valley. The 1st Cavalry Division meanwhile cleared both sides of San Juanico Strait, and by shore-to-shore movements instituted extensive patrolling on southwestern Samar. Similar amphibious operations took some of the cavalrymen around the northeastern tip of Leyte past Babatngon to Barugo on Carigara Bay.78 Other units of the division, driving northwest from Tacloban into rugged mountainous terrain along the Diit River, moved through the northern reaches of the Leyte Valley to San Miguel, southeast of Carigara.

At this time several counterattacks in strength and increasing opposition in general indicated that the Japanese intended to make a determined stand at Carigara, a key terminus of the valley roads leading from Leyte's east coast. The X Corps, therefore, consolidated its units in preparation for a co-ordinated attack on Carigara by both the 1st Cavalry and 24th Divisions, moving along the shores of Carigara Bay and up Highway No. 2. On 2 November the combined attack was launched and the X Corps units moved forward only to discover that the town had been abandoned by the enemy. It became apparent that under cover of a successful delaying action, the Japanese had withdrawn to stronger positions in the high ground behind Carigara in an effort to spar for time until their reinforcements could be brought up from Ormoc.79

As the American forces pressed forward from the east coast of Leyte, the Japanese continued to move large reinforcements into Ormoc. There were indications late in November that the Japanese were sending troops of the 55th Independent Mixed Brigade from faraway Jolo in the Sulu Archipelago80 in addition to the re-

[228]

mainder of the 1st and 26th Divisions which arrived from Luzon between 9 and 11 November.81 Allied planes were not idle during these Japanese convoy movements. The entire enemy cargo of artillery and equipment which was sent in a subsequent shipment was destroyed in a savage Allied aerial attack and all five ships of the convoy including its destroyer escort were sunk. To circumvent the persistent attacks upon their convoys, the Japanese set up a barge shuttle system between Cebu and Ormoc to carry in troops from the Visayas under cover of darkness.82 The enemy also turned Leyte's seasonal storms and unceasing rains to advantage by operating his convoys at full speed while the weather prevented U.S. planes from leaving their carriers.

The heavy and continuous tropical rainfall became a serious impediment to the scheduled progress of operations. Important roads were turned into rivers of mud, slowing and at times halting the movement of supplies to the advancing forces. Communication lines were constantly disrupted and contact between units was difficult to maintain. The poor drainage and swampy soil continued to delay the conditioning of the vital airstrips, leaving ground troops without adequate land-based air support for combat operations.

Again the key to the situation in the initial phase of the operation, as General MacArthur had anticipated, was air power. Not only was it important to provide adequate air cover for his ground operations but the immediate reduction of the enemy's defensive air strength was imperative. Realizing that the general strategic situation had changed, General MacArthur requested that the carriers of the Third Fleet continue to be used to give his forces additional air cover.

It is now evident that the enemy has decided to make a decisive stand in western Leyte in order to delay our further advance in the Philippines thereby gaining time for preparation for the defense of Luzon. The Leyte phase must be pressed with the utmost vigor to completion. It is therefore essential that the arrival of convoys now enroute be on schedule. The hazard to convoys must be accepted as a legitimate risk of war. In this general connection I am convinced that the support of fast carriers is likewise essential to current operations until Army air is established in Leyte in sufficient strength to hit all enemy air bases in the Philippines in full neutralizing force. I am requesting Admiral Nimitz to utilize the Third Fleet accordingly.83

The dangerous shortage of airpower and the rapidly increasing opposition from a greatly strengthened enemy made it necessary for General MacArthur to bring additional forces into Leyte. Toward the middle of November the 32nd Division and the 112th Cavalry Regimental Combat Team, both veterans of many previous campaigns in the Southwest Pacific, were sent into action in the zone of X Corps.

[229]

Approach to the Ormoc Corridor

When it became apparent that the Japanese were committing the bulk of their forces in an offensive northward along the Ormoc Corridor, General Krueger decided to hold the initiative by constant pressure on all fronts. His strategy contemplated launching a strong assault southward from the direction of Pinamopoan while simultaneously pushing forward with units of both the X and XXIV Corps in order to penetrate into the Ormoc Valley. As soon as practicable, another arm of his forces would commence a drive northward along the coast from Baybay. If practicable, the vulnerable west flank of the Japanese would be attacked by an amphibious landing at Ormoc.

After occupying Carigara on 2 November, elements of the X Corps advanced westward to Capoocan and Pinamopoan, at the northern end of the Ormoc Corridor. (Plate No. 64) The 24th Division began an advance south from Pinamopoan down Highway No. 2 toward Valencia and Ormoc.84 In the Limon area, however, the Japanese put up a stubborn fight from strong positions on the high ground of Breakneck Ridge and the progress of the division was bitterly contested. It was not until 14 November that the ridge defenses were overcome and the enemy forces cleared from the area. At this time, the exhausted elements of the 24th Division were relieved by fresh troops of the newly arrived 32nd Division which took up the fight for control of the Ormoc Corridor.

In an effort to approach the eastern flank of the Corridor, the 1st Cavalry Division, with units of the 24th attached, began a concerted drive southwest from the Jaro-Carigara road in the Mt. Badian sector. The mountainous terrain and torrential rains, combined with well-planned and fierce Japanese counterattacks, made progress exceedingly difficult. Even after the 112th Cavalry was added to the division on 14 November, the advance through the wild, hilly country against an unyielding enemy remained slow and arduous, and continued into December.

In the XXIV Corps sector the 7th Division reached Baybay, on the Camotes Sea, early in November.85 Other elements of the 7th Division probed enemy positions in the mountains west of Dagami and Burauen. By the 25th of November, the bulk of the 7th Division had displaced to the west coast of Leyte. The 96th Division, taking up the attack in the central sector, moved westward in a series of strong actions, and then was halted by deeply intrenched enemy forces. At this point the Japanese were trying to hold in order to prepare a counterattack and all available remnants of the Japanese 16th Division were placed in

[230]

PLATE NO. 64

Ormoc-Carigara Corridor, 3 November-25 December 1944

[231]

positions well chosen to guard the southeastern approaches to the Ormoc Corridor. One regiment of the U. S. 96th Division moved northwestward from Dagami to outflank enemy positions and to secure the mountain passes leading westward in the Alto Peak area.

On 18 November, the 11th Airborne Division arrived on Leyte and was committed to action in the XXIV Corps area on the left flank of the 96th Division. Its mission was to control the passes into Leyte Valley and to secure the western exit from the mountains into the coastal corridor running along Ormoc Bay thus protecting the flank of the 7th Division. The paratroopers had to change practically overnight from an airborne to a mountain division as they moved across the rough terrain west of Burauen over a twisting, ill-defined road that wound toward Albuera on Leyte's west coast.

It was intended that the 11th Airborne Division ultimately link up with the 7th Division advancing north from Baybay. By 15 November, elements of the 7th Division had pushed their way to Damulaan about 13 miles north of Baybay. Here, it seemed, the Japanese planned to hold the Palanas River line just above Damulaan while they attempted to counterattack eastward toward Burauen. The 7th Division, therefore, consolidated its forces at Damulaan and prepared for a major drive northward in an effort to break through the enemy's river defenses. The concentration of the 7th Division on the west coast of Leyte compelled the Japanese to divert large forces from Ormoc and move them southward toward Damulaan. This not only helped disrupt the enemy's plan to recoup his losses by a drive eastward across the mountains but also served to weaken his garrison in the Ormoc area.