| Battle of Ormoc Bay | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Pacific Theatre of World War II | |||||||

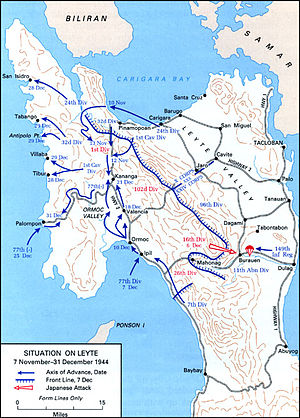

Leyte campaign, November-December 1944 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 6 ships sunk | 29 ships sunk 1 submarine sunk 1 patrol boat sunk |

||||||

The Battle of Ormoc Bay was a series of air-sea battles between Imperial Japan and the United States in the Camotes Sea in the Philippines between 11 November and 21 December 1944, part of the Battle of Leyte in the Pacific campaign of World War II. The battles resulted from Japanese operations to reinforce and resupply their forces on Leyte and U.S. attempts to interdict them.

Contents[hide] |

[edit] Background

After gaining naval control over the Western Pacific in mid-1944, the Allies attacked the Philippines in October, landing troops at Leyte Gulf on the east side of Leyte on 20 October 1944. The island of Leyte was defended by about 20,000 Japanese; American General Douglas MacArthur thought that the occupation of Leyte would be only a prelude to the major engagement on Luzon. For the Japanese, maintaining control of the Philippines was essential because their loss would enable the Allies to sever their oil supply line from Borneo.

The Imperial Japanese Navy responded to this attack with a combined fleet attack that led to the Battle of Leyte Gulf between 23 October and 26 October. In this massive naval engagement, the Japanese Navy was destroyed as a strategic force. However, this was not at first clear, and the Japanese commander in the Philippines, General Tomoyuki Yamashita, believed that the United States Navy had suffered severe casualties and that the Allied land forces might be vulnerable. Accordingly, he began to reinforce and resupply the garrisons on Leyte; over the course of the battle the Japanese ran nine convoys to the island, landing around 34,000 troops from the 1st, 8th, 26th, 30th, and 102nd divisions. Ormoc City at the head of Ormoc Bay on the west side of Leyte was the main port on the island and the main destination of the convoys.

Decryption of messages sent using the PURPLE cipher alerted the Allies to the concentration of Japanese shipping around Leyte, but they initially interpreted this as an evacuation. However, by the first week of November the picture was clear, and the Allies began to interdict the convoys.[1]

[edit] Operations

[edit] TA-3 and TA-4 (Japanese)

On 8 November and 9 November, the Japanese dispatched two convoys from Manila to Ormoc Bay.[2] The convoys were spaced one day apart so that the destroyers escorting the first convoy could double back and escort the second. However, the convoys were spotted on November 9 and attacked by land-based aircraft of the Fifth Air Force. On 10 November the 38th Bomb Group, based on Morotai, sent 32 B-25 Mitchells escorted by 37 P-47 Thunderbolts to attack TA-4 near Ponson Island. Reaching the convoy just before noon, the B-25s attacked at minimum altitude in pairs, sinking the two largest transports, disabling a third, and sinking two of the patrol craft escorts, at a cost of seven bombers, for which the group was awarded the Distinguished Unit Citation.

On 11 November U.S. 3rd Fleet commander Admiral William F. Halsey ordered an attack by 350 planes of Task Force 38 on the combined convoys.

Four destroyers — Shimakaze, Wakatsuki, Hamanami and Naganami — and three transports were sunk. Rear Admiral Mikio Hayakawa went down with Shimakaze.[3]

[edit] TA-5 (Japanese)

Convoy TA-5 left Manila on 23 November for Port Cataingan and Port Balancan. Of the six transports, five were sunk by air attack.[2]

[edit] U.S. destroyer sweeps

Bad weather in late November made air interdiction less effective, and the U.S. Navy began to send destroyers into Ormoc Bay. Canigao Channel was swept for mines by USS Pursuit and Revenge, and the four destroyers of Destroyer Squadron 22 (DesRon 22) under the command of Captain Robert Smith (Waller, Pringle, Renshaw and Saufley) entered the bay, where they shelled the docks at Ormoc City.

An Allied patrol plane radioed a message to the division noting that a surfaced Japanese submarine (the I-46) was south of Pacijan Island and heading for Ormoc Bay. The division headed south to intercept; and, at 01:27 on 28 November, Waller's radar picked up the target just off the northeast coast of Ponson Island. Waller disabled the submarine with her first shots and, unable to submerge, I-46 could only return fire with her deck guns until she sank at 01:45.[4]

[edit] TA-6 (Japanese)

Two transports escorted by three patrol vessels left Manila on 27 November. They were attacked by American PT boats in Ormoc Bay on the night of 28 November and by air attack as the survivors left the area. All five ships were sunk.[2]

Another U.S. destroyer sweep on the night of 29 November–30 November in search of a reported convoy resulted only in the destruction of a few barges.

[edit] TA-7 (Japanese)

A convoy of three transports departed Manila on 1 December, escorted by destroyers Take and Kuwa under the command of Lieutenant Commander Masamichi Yamashita. Two groups of transport submarines also took part in the operation.[5]

The convoy was docked at Ormoc City when it was engaged at 00:09 on 3 December by three ships of U.S. Destroyer Division 120 (DesDiv 120) under the command of Captain John C. Zahm (Allen M. Sumner, Cooper and Moale).

The U.S. ships sank the transports as they were unloaded but came under heavy attack from Yokosuka P1Y "Frances" bombers, shore batteries, submarines that were known to be in the harbor, and the Japanese destroyers. Kuwa was sunk and Commander Yamashita was killed. Take attacked Cooper with torpedoes and escaped, though with some damage. Cooper sank at about 00:15 with the loss of 191 lives (168 sailors were rescued from the water on 4 December by PBY Catalina planes). At 00:33, the two surviving U.S. destroyers were ordered to leave the bay, and the victorious Japanese successfully resupplied Ormoc Bay once more. This phase of the Battle of Ormoc Bay has gone down in history as the only naval engagement during the war in which the enemy brought to bear every type of weapon: naval gunnery, air attack, submarine attack, shore gunnery and mines.[6]

[edit] Ormoc Bay U.S. troop landings

On 5 December 1944, U.S. Marines made a landing at San Pedro Bay, 27 mi (43 km) south of Ormoc City. The landing craft and support vessels came under sustained kamikaze attack. Fifteen craft were sunk, and destroyers USS Mugford and Drayton were hit, suffering about 50 casualties.[7][8]

On 7 December, the 77th Infantry Division, commanded by Major General Andrew D. Bruce, made an amphibious landing at Albuera, 3.5 mi (5.6 km) south of Ormoc City. The 77th Division's 305th, 306th, and 307th Infantry Regiments came ashore unopposed, but naval shipping was subjected to kamikaze attacks, resulting in the loss of destroyers Ward and Mahan.[1]

[edit] Other operations

All five transports of convoy TA-8 were sunk on 7 December by air attack, and the escorting destroyers Ume and Sugi were damaged.

Convoy TA-9 entered the bay on 11 December and landed troops, but two escorting destroyers, Yūzuki (by air attacks) and Uzuki (by PT boats), were sunk and the third, Kiri, was damaged.[2]

[edit] Aftermath

By fighting this series of engagements in Ormoc Bay, the U.S. Navy was eventually able to prevent the Japanese from further resupplying and reinforcing their troops on Leyte, contributing significantly to the victory in the land battle. The final tally of ships lost in Ormoc Bay is: U.S. — 3 destroyers and 1 APD 60 (high speed transport) plus two LSMs; Japan — 6 destroyers, 20 small transports, 1 submarine, 1 patrol boat and 3 escort vessels.

Historian Irwin J. Kappes argued that naval historians have unjustly neglected the importance of these engagements, writing:

"In the end, it was the rather amorphous Battle of Ormoc Bay that finally brought Leyte and the entire Gulf area under firm Allied control. From 11 November 1944 until 21 December, the combined efforts of Third Fleet carrier planes, Marine fighter-bomber groups, a pincer movement by the Army’s 77th Division and the First Division plus a motley assortment of destroyers, amphibious ships and PT boats trounced the now semi-isolated Japanese in a series of skirmishes and night raids. And because of poor weather conditions air support for most of these surface actions was almost non-existent."[9]

[edit] Notes

- ^ a b Anderson, Charles R.. Leyte. The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 72-27. Retrieved 2006-05-25.

- ^ a b c d "Leyte Reinforcement Convoys 23 October to 13 December 1944: Operations "TA-1" to "TA-9"". Retrieved 2006-01-06.

- ^ Allyn D. Nevitt. "Shimakaze: Tabular Record of Movement". Retrieved 2006-01-06.

- ^ US Department of the Navy: Naval Historical Center. "Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships: Waller". Retrieved 2006-01-06.

- ^ Allyn D. Nevitt. "Kuwa: Tabular Record of Movement". Retrieved 2006-01-06.

- ^ US Department of the Navy: Naval Historical Center. "Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships: Cooper". Retrieved 2006-01-06.

- ^ US Department of the Navy: Naval Historical Center. "Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships: Mugford". Retrieved 2006-01-06.

- ^ US Department of the Navy: Naval Historical Center. "Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships: Drayton". Retrieved 2006-01-06.

- ^ Kappes, Irwin J.. "A New Look at the Battle for Leyte Gulf". Retrieved 20011-11-21.

[edit] References

- Griggs, William L. (1997). Preludes to Victory: The Battle of Ormoc Bay in WWII. ISBN 0-9659837-0-6. (280-page book)